Articles

Editor’s Picks

K-12

The Digital Divide Is 99.2% Closed. For EducationSuperHighway, It’s Been an 8-Year Journey.

By Henry Kronk

October 23, 2019

EducationSuperHighway, a non-profit dedicated to bridging the digital divide in American public schools, launched in 2012. Their initial research prompted former President Barack Obama to launch the ConnectED initiative in June of 2013. At the time, the two entities set a goal to get 99% American schools connected to broadband internet with a minimum speed and bandwidth of 100 kbps by August of 2020. On October 22, the organization announced that 99.2% of public schools had met the threshold.

Many schools, districts, and even the state of Arkansas, furthermore, have achieved 1 Mbps. In their annual report, EducationSuperHighway even discussed schools reaching toward 1 Gbps and even 10 Gbps.

These gains have come thanks to a massive coordination effort spearheaded by EducationSuperHighway and its dozens of partners that brought together internet service providers, philanthropic organizations, schools, districts, 81 different governor’s offices in 50 states over 8 years, the federal E-Rate program, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

“I think E-rate modernization has been one of the great success stories of public policy in the last decade,” said EducationSuperHighway founder and CEO Evan Marwell. “It was clearly something where the federal government said, ‘Look, we have a program. It’s not getting the job done, the way we need it to get done.’ They used data to understand what the challenges were and what the opportunities for improvement were. And they also leveraged open data to and allow other actors to play a role.”

EducationSuperHighway Launched In 2012 to Bridge the Digital Divide

The Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Services Fund, known commonly as E-Rate, was initiated during the Clinton administration to support, in part, internet access and telecom services at American public schools and libraries.

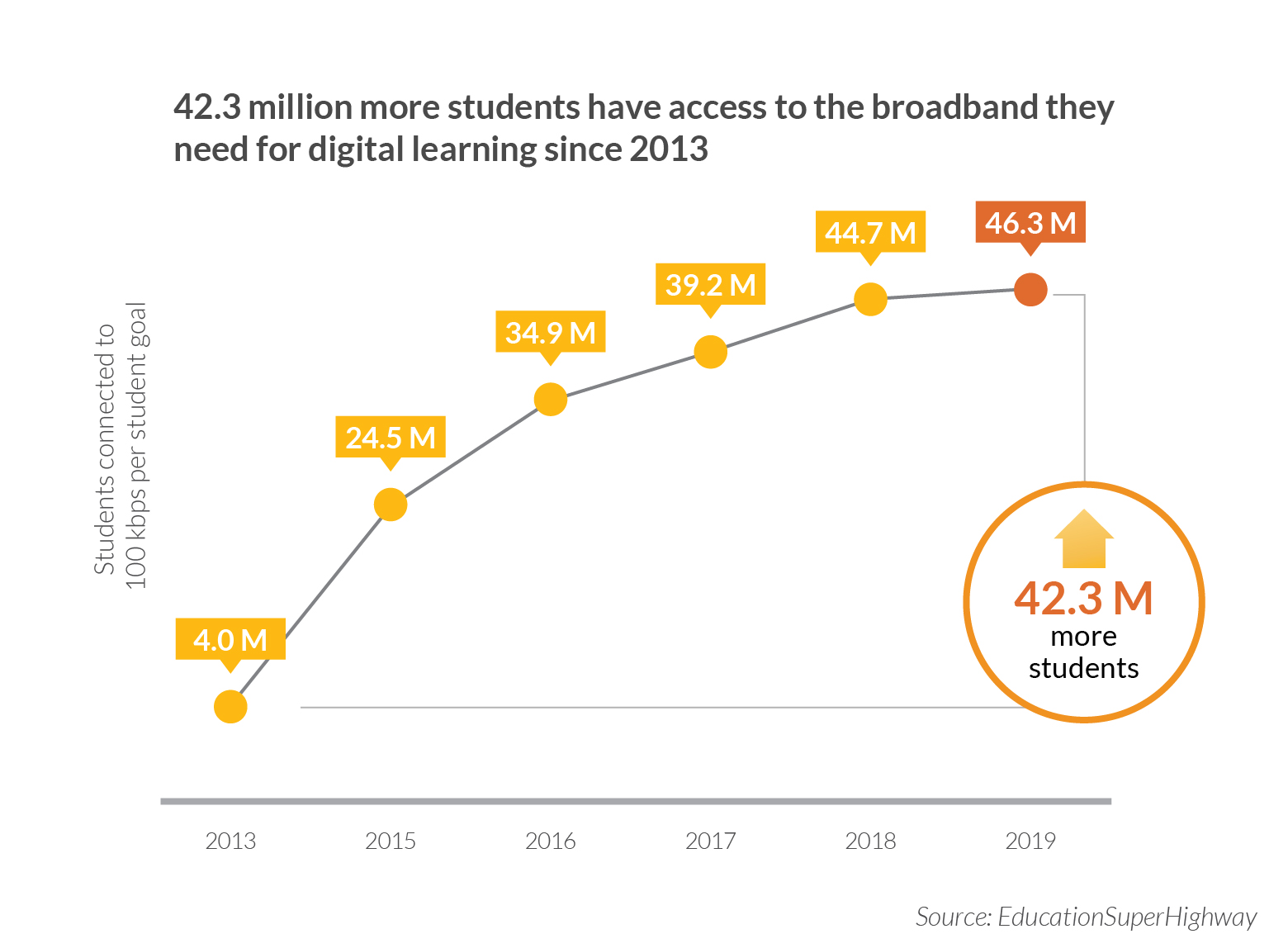

But in 2012, E-Rate wasn’t working the way it was intended. At the time, it was determined that a connection speed and bandwidth of 100 kbps per student would be sufficient to support digital learning in the classroom. When EducationSuperHighway opened shop, they found that just 4 million out of 47 million students had access to that internet service.

More than 22,000 schools also lacked a fiber-optic connection that would allow them to boost their internet service to that speed.

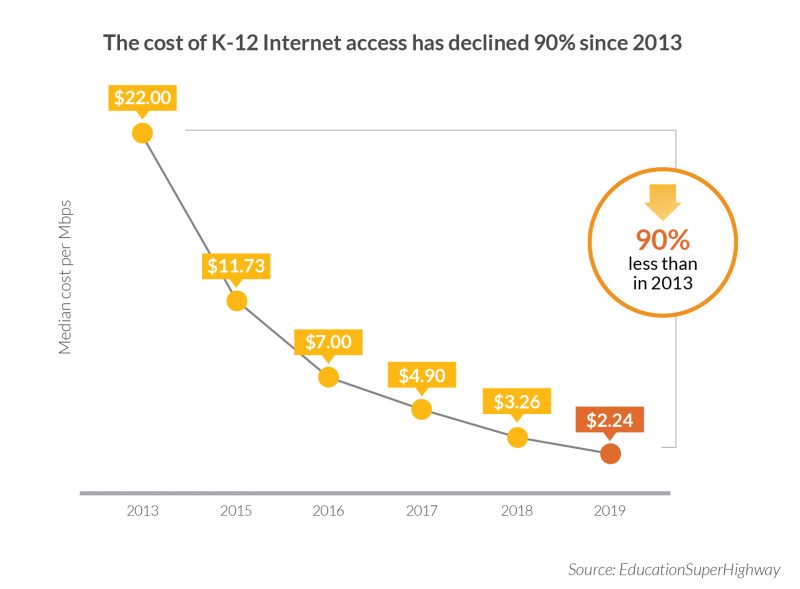

The internet that did exist was delivered to end-users primarily through wired connections. Just 25% of schools reported they had implemented Wi-Fi internet. And, finally, districts were paying an average of $22 per Mbps per month.

“Since then, there has been this unbelievable bipartisan effort to change that situation,” Marwell said. “And it all started with President Obama launching the ConnectED initiative in 2013 with the goal of connecting 99% of American schools to high speed broadband.”

Coordinating Between The FCC, ISPs, and Districts

The first step involved the FCC ramping up their support for E-Rate.

“At the time, only $1.4 billion a year was being invested by the FCC and broadband in America’s public schools,” Marwell said. “Today, that number is $4 billion a year, so they significantly increase their investment. Second, they changed the rules to allow school districts to use those funds to get fiber optic connections built to those 22,000 schools.”

According to Marwell, the FCC also made another crucial move: they made data from the program, including the prices individual districts paid to internet service providers, publicly available. That has led to an overall 90% reduction in the cost of broadband for schools over the past eight years.

Evan Marwell: We told school districts, ‘You know, you have neighboring districts that are dealing with the same service providers, and they’re getting a much better deal.’ So we set schools’ expectations higher. But when we talked about the price going down, we didn’t want to see districts go from paying $1,000 a month to paying $250 a month, but, rather, that they were getting more bandwidth and speed for that same $1,000.

Then we created market forces. We went out to the service provider community and said, ‘Look, here’s what everybody’s buying today. And here’s the deal: we’re giving you a lead generation list. Go get after these schools and give them your best deal. And then on the flip side, we told the schools, ‘Here are the best deals that are out there, make sure you contact those service providers.’ So it really was about creating higher expectations for the school district, and then creating a more efficient market on both sides. Our message was always to get more bandwidth for your budget. It wasn’t save money. It was more bandwidth for your budget because more bandwidth was the goal.

We never asked the ISPs to give up any revenue. We said, ‘Look, we don’t want you to make any less money than you’re making today. We just want you to give schools a lot more bandwidth.’ And they responded. It was truly a win-win opportunity.

Taking the Issue to the Governors

These steps represented just the initial groundwork that needed to be laid. Once EducationSuperHighway and its partners established transparency between ISPs and districts, they still needed to increase the fiber-optic infrastructure to make 100 kbps per student possible, steps that would be needed to bridge the digital divide.

Evan Marwell: The challenge then became ‘Okay, how do we make sure those resources get used well, and that they actually result in schools getting upgraded?’ That took us to the next phase of the story, which involved 81 governors in all 50 states joining forces to make this a reality to upgrade all of their schools. The combination of governor leadership and participation by service providers built out literally tens of thousands of miles of fiber to schools.

That has led us to a point today where 99% of our schools in America have a high-speed fiber connection, where 99.2% of school districts are meeting that goal set by the FCC of 100 kbps per student of internet access.

The average cost of 1 Mbps has fallen from $22 per month in 2013 to $2.24 today. According to a report released by EducationSuperHighway on October 22, 87% of teachers report implementing digital learning multiple times per week. 96% of admins and teachers say this digital instruction has had a positive effect.

The work of bridging the digital divide might be drawing to a close, but next steps naturally follow. In 2017, the FCC bumped up their target of 100 kbps to 1 Mbps per student to satisfy current needs. That is now a reality at 38% of American school districts, and that figure has continued to increase.

Evan Marwell: This is absolutely mission accomplished. When we started back in 2012, 99% was our goal, and we have hit it. I’m proud to say we did it a year ahead of schedule. The one thing we have to keep in mind, though, is that there is still that 1% who are on the wrong side of the digital divide, and we’re going to do everything we can over the next 10 months before we sunset EducationSuperHighway to help them.

The other thing, though, is that the 100 kbps per student goal—that really was just the starting point. 100 kbps allows teachers and students to start using digital learning in their classroom. What it doesn’t do is allow every teacher in every classroom to use digital learning whenever they want. The FCC understood that. And that’s why they set out a second goal of 1 Mbps per student goal.

When we started this work, you know, the goal was to bring connectivity to every classroom. But the real objective was to enable digital learning. I’m just super excited that we, for the first time, have some data that suggests that that’s actually happening.

A New Approach to Public-Private Action

None of this progress with the digital divide would have been possible without the massive collaboration brokered by EducationSuperHighway, one that involved participation by governors across the political spectrum.

Evan Marwell: As I reflect back on the work that we’ve done over the last seven years, I think that we may have pioneered a new approach to working with government to help solve problems at scale. Government’s not necessarily the place that innovation happens, right? But there’s a lot of innovation on social problems of all kinds happening in the non-profit sector and, to some extent, in the for-profit sector.

Now, the non-profit sector is not that good at getting to scale. But it turns out that the government is very good at getting things to scale when they have the right solutions and the right partners. I think we did some some unique things in how we partnered with the government that enabled us to get the innovation, but then also get the government to be our scaling partner.

The first was that we used data to define the problem in a way that the government believed it, particularly the governors in all 50 states. The second thing we did is made sure that we defined the right role for government. That was to use their bully pulpit to set goals and to be the distribution channel for getting to scale. But we didn’t ask them to actually execute, because the government just doesn’t have the human capital to be able to do that.

We provided all that execution capacity, tracked the data, and tracked progress. We held the government accountable for achieving these goals by every year issuing the status reports, but frankly, more importantly, celebrated their success so that the governors, the federal policy makers, they all felt as though this was work that they were doing. They were making progress, and they were getting credit for that progress. So it’s a little bit of a different twist on how people have traditionally viewed the role of government. But I think it’s something that lots and lots of non-profits could leverage as a model in lots of different issues, as long as they understand what the government can do.

The digital divide has nearly been bridged completely. But as appetite for digital learning and higher internet speeds and wider bandwidth increase, the work set in motion by EducationSuperHighway will continue for the foreseeable future.

Featured Image: Needpix

[…] Launching successful online degree programs requires expertise and resources not typically found within most institutions – innovative instructional design and development, technology-informed advertising and marketing, and intentional and focused inquiry management. Faced with the challenge to adapt and evolve as modern universities, many institutions are faced with build or buy decisions. Do you create infrastructure internally or do you partner with an Online Program Management (OPM) company? […]