Articles

Editor’s Picks

Higher Education

A Bipartisan Group of Senators Want to Collect More Student Data. It Won’t Be Easy.

By Henry Kronk

May 18, 2019

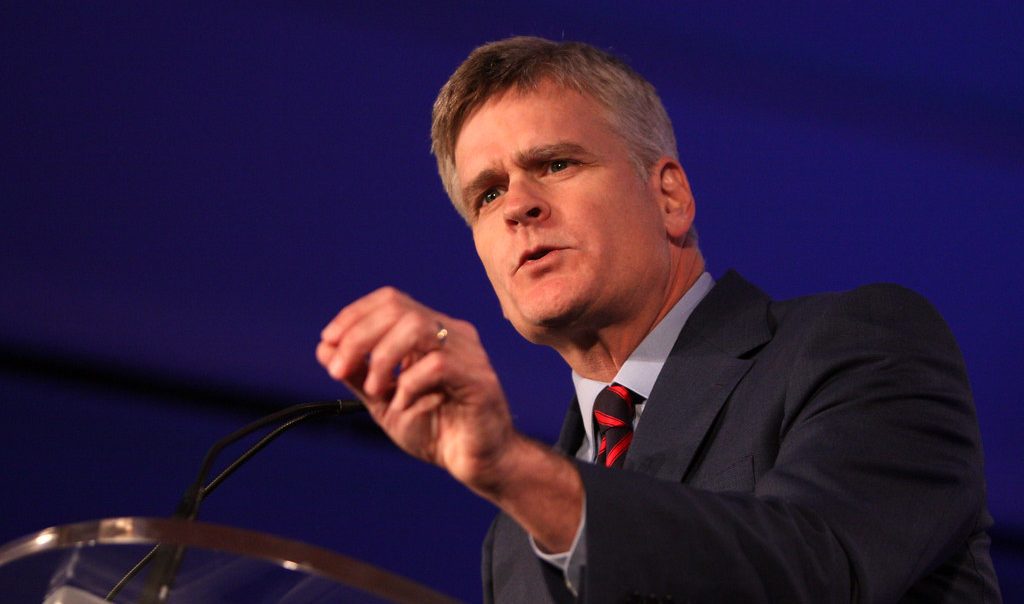

In March, a bipartisan group of senators led by Bill Cassidy (R-La.) reintroduced the College Transparency Act (CTA). The bill would expand the student data collection practices of the National Center for Education Statistics, call for the collection of key college and post-graduation performance indicators, and streamline the reporting of the data. The Institute for Higher Education Policy has two reports out this week as part of their Protecting Students, Advancing Data: A Series on Data Privacy and Security in Higher Education project. The first examines existing federal data protection and security laws, and the second examines the case of Louisiana, which implemented a similar data collection bill in 2014 and quickly faced unintended consequences.

Sen. Alexander Wants HEA Rewrite by the End of the Year

There is a good deal of momentum behind education reform in 2019. Former Department of Education Secretary and Senate HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) delivered a speech at the American Enterprise Institute in February in which he made rewriting the Higher Education Act (HEA) a priority this year. Among the upgrades to the HEA, he mentioned the CTA among six other initiatives that he believed would make strong additions to the rewrite.

Rewriting the HEA will be needed to proceed with the passage of the CTA. The Student Unit Record system was banned with an amendment to the HEA in 2008. Two years later, Senate investigators began to find on their own that a disproportionate amount of graduates who attended certain for-profit colleges were defaulting on their student loans.

It’s true that many entities already track some student data. As Joanna Lynn Grama writes in her IHEP report, “While data is already available—colleges and universities, multistate collaboratives, private organizations, and the federal government all collect, share, and use different types of postsecondary data—the infrastructure is fragmented, disconnected, and uncoordinated. As a result, the available dataset is inadequate to meet the needs of all who depend on it.”

If an all encompassing data system were in place—one that tracked what students actually paid for tuition, their academic performance, the salaries they earned after graduation, and their ability to repay their student loans—many may not have opted to learn with fraudulent companies in the first place.

But with a great amount of data comes great responsibility. A database that size, which would contain sensitive personally identifiable information (PII), such as social security numbers, would present a massive target for hackers.

There are already numerous pieces of legislation in place to protect citizen data collected by federal bodies. Grama identifies two that pose the biggest challenges when it comes to conforming to preexisting laws: the Privacy Act of 1974 and the E-Government Act of 2002. Other legislation, like the Family Educational Rights and Protection Act and numerous state laws, would also figure into the equation.

Student Data Case Study: Louisiana

According to a twin IHEP report authored by Rachel Anderson and also released this week, a potentially bigger hurdle needs to be overcome: public understanding and acceptance. To highlight this, Anderson holds up the example of the state of Louisana (home to Sen. Cassidy), which was set to pilot the inBloom data management service in 2014.

While the Louisiana State Legislature had reached an agreement, when policymakers began to engage public stakeholders, pushback emerged. Anderson quotes State Superintendent John White, who, following a “contentious” 2013 board meeting, said, “I heard the comments from parents who had concerns, and I said ‘Look, this isn’t something we have really talked about in public to a great extent.’ I’m not talking just about inBloom, I’m talking about the entire question of how we store data and student info.”

In response, the state passed two laws. Act 837 sought to safeguard student privacy by “prohibiting districts from sharing identifiable student data with any entity outside the district without written consent.” Act 677, meanwhile, also required districts to be transparent about what data management services they used, how they used the data, and with whom they shared it.

According to Anderson, both laws, though well-intended, proved disruptive and potentially dangerous. She writes, “reports of disruptions in school functioning and confusion about how the law’s provisions could be reported quickly emerged after the law’s passing. Rapides Parish School Board counsel James Downs told the Board’s Education Committee, ‘I don’t see, frankly, how schools are going to function without the general release of information. It’s impossible actually.’”

Act 677, meanwhile, according to a Facebook post by State Treasurer John Schroeder, unknowingly “presented a roadmap to hackers.”

Establishing a National Higher Ed Student Database Will Not Be Easy

As the two IHEP reports conclude, it is very difficult to enact beneficial student records legislation.

Grama concludes, “The amount of student and family PII collected by and linked within a federal SLDN could give unprecedented insight into questions of college access, affordability, and student outcomes. Despite the benefits of ensuring access to accurate, timely, and high-quality aggregate data about student outcomes, ensuring the adequate security of such a system and protecting the privacy of individuals who have identifiable data in that system are of utmost importance. The 2019 CTA acknowledges these concerns and provides a solid foundation for a security and privacy-minded federal postsecondary SLDN with the direction that the NCES develop and maintain such a system consistent with federal information security and privacy laws.”

Featured Image: Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.). Image by Gage Skidmore, Flickr.

No Comments