Editor’s Picks

Interviews

Capturing the Past in Virtual Reality: An Interview with Simon Che de Boer

By Henry Kronk

September 14, 2018

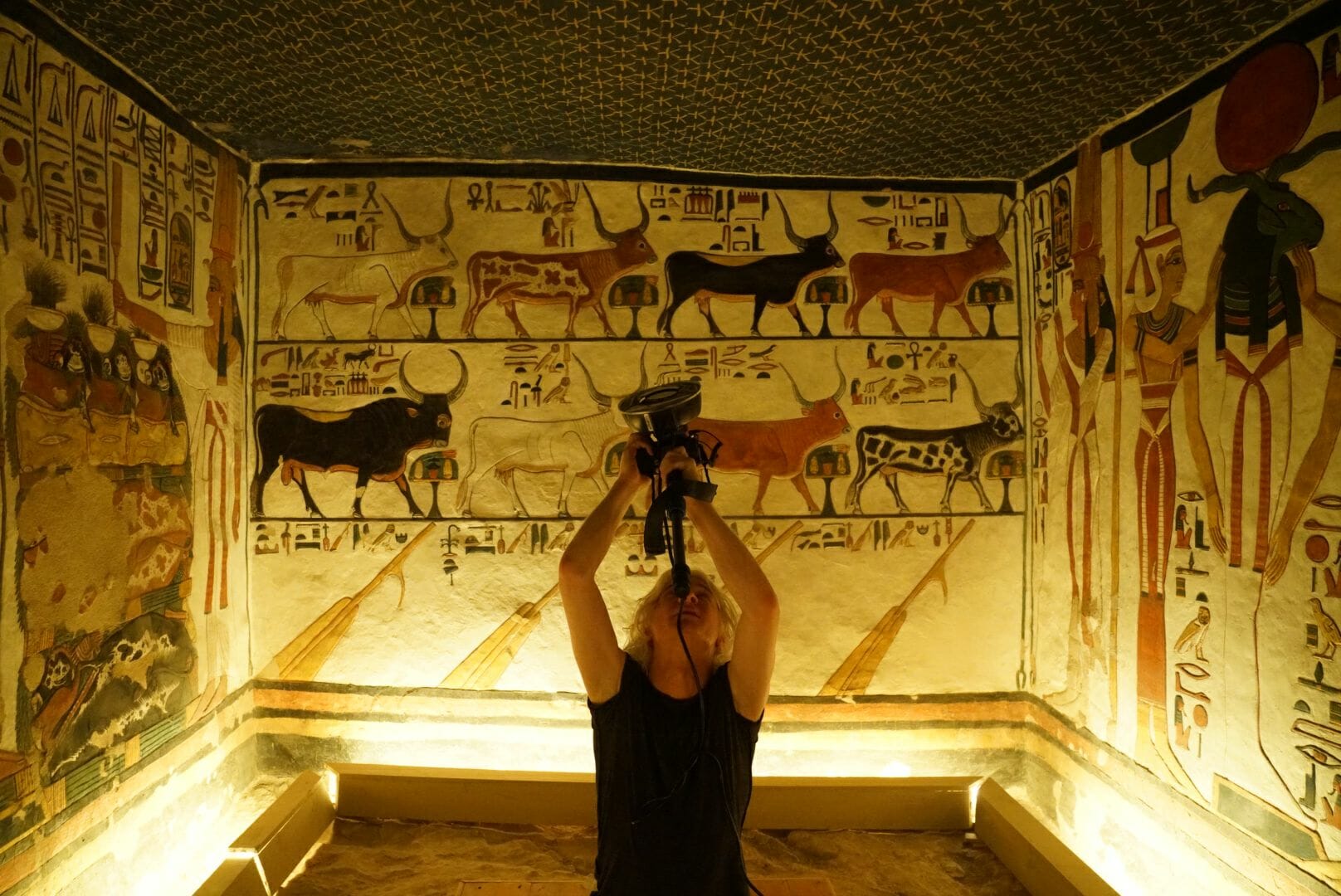

Earlier this summer, eLearning Inside reported on a virtual reality experience that would go on to top charts on Steam and become a huge success for CuriosityStream, the platform on which it was offered. Nefertari: Journey to Eternity was created in large part by Simon Che de Boer, a Kiwi who describes himself as a jack-of-all-trades. Over the past five years, he, along with his team at Reality Virtual, have been pushing the edge of what is possible in virtual reality and virtual environment creation. They hope to empower photographers around the world to capture and preserve environments of cultural and historical significance. And for Che de Boer, the process started with tragedy.

“About five years ago, I was in a house fire,” he said via teleconference. All of his personal belongings were destroyed. “I got into this space where I needed to find a way to cope with this traumatic experience. And I thought I’d essentially deal with it.”

“I thought, ‘Could I use my old family photographs of my place to recreate my old house so my daughter and I could go home?’ I didn’t know anything about virtual reality, I just knew how to put things together. So I spent many years working on a pipeline of how to do things. Along the way, I discovered photogrammetry. So when I was getting into it, photogrammetry was very new, no one was doing environments.”

Translating Image to Virtual Environment with Photogrammetry

The process would lead to breakthroughs in virtual environment creation, involve machine learning algorithms dealing with vast data sets, and developments that will, with luck, become indispensable for purposes of cultural preservation and education around the world.

An early step was the use of photogrammetry. The process involves taking hundreds to thousands of photographs of objects or environments from set positions, moving incrementally with each new image. Upwards of 4,000 images went in to the virtual rendering of Nefertari’s tomb.

Che de Boer then used software to compile those images into a virtual space. “The first thing we achieved was getting billions of points to work in real time,” he said. We’ve achieved many other new things since then. We can get the computer to help fill in the gaps. It understands what a wall is, what a chair is, all that stuff. We can use that to fill in areas that might be considered incomplete.”

From there, Che de Boer and his team began to manipulate the images en masse in order to create a more stylized version of the virtual environment made up of raw images. That process has recently developed into an application that Che de Boer believes will become instrumental across media.

“Unbaking”

“The problem with photogrammetry currently is what we call baked lighting,” he said. In other words, when a photographer snaps an image, a whole slew of qualities are also encapsulated—or baked—into it. These include the angle of lighting, tones of color, hue and saturation, whether a surface appears shiny or matte, etc.

“We are able to remove that using a custom photograph rig that we have. We’ve actually managed to train a network to look at a normal photograph and remove all the lighting qualities in it. So it can use it as just a base texture. And that’s where base rendering comes in. Under other circumstances, it takes hundreds of graphics artists hours upon days to prepare these textures.”

The implications are groundbreaking. Using Che de Boer’s technique, a film studio need not wait for the weather to comply for an outdoor shot. They could merely capture the environment and then shoot all the action in a studio.

For purposes of education and cultural preservation, it has even greater potential.

“It means that average people with their cameras can go out to historical sites and capture them, but make them such a high quality that they can create a virtual environment,” Che de Boer said.

A Democratized Vision for Virtual Reality Creation

“What I’m personally excited about is encapsulating a place all around the world for education. I can’t be everywhere. We will provide our pipeline and our service and will essentially allow photographers with much less equipment than I use to go out and capture these environments. We’re looking at a way to make sure those photos get back to those photographers, so they make money on them essentially.”

One of these virtual reality projects is already underway in Che de Boer’s home country of New Zealand. In 2010 and 2011, a 7.1 and 6.3 magnitude earthquake (respectively) struck Christchurch, which was at the time the country’s second largest city. The two seismic events killed hundreds of people and devastated the urban center. Numerous historical buildings were destroyed, including two cathedrals.

Che de Boer’s company, Reality Virtual, is currently asking Christchurch citizens (current and former) to send in images they have of these historic sites in order to rebuild them virtually. The company is already collaborating on similar projects elsewhere.

“We’re already talking with parties all around the world who are scanning churches,” Che de Boer said. “Beautiful stuff is happening in Cape Town University [in South Africa]. I’m off to the south of France at some point soon. Many people are beginning to share with us their data sets. So we’re starting to do little passion projects to show how we can use their data to make really immersive virtual reality experiences.”

The vision behind is the work is to empower photographers to do these virtual environment projects, but to also allow them to retain ownership as well.

“We’re leading by example. We’re saying to people ‘give us your data sets, we’ll put them under a trust.’ Eventually we want to have a blockchain repository so anyone who provides a photo, it’s tagged, and have it automated.”

“We want data sets to be under a public trust, but not necessarily distributable. One thing that annoys me with certain jobs is when a company hires me to take a bunch of photos that no one will ever see those again. If the company goes bankrupt, those photos are lost. My biggest thing is archiving and protecting under a public trust those data sets so if, for whatever reason, an entity isn’t able to distribute those in the future, they won’t be lost.”

“If that happened in Egypt, the only other option is for someone to go back into Nefertari’s Tomb and take another 4,000 photographs. As soon as you do that, you have degradation of the environment.”

This effort—an online repository of photogrammetry data sets which preserves certain digital rights—will make up Che de Boer’s upcoming efforts.

“The artists should be getting paid, the people who are going through the trouble to go out and photograph these sites, which is quite a process, should be receiving royalties for the work they’ve done.”

From there, he’s hoping to work with the virtual reality community to fill in some gaps. And one of those gaps involves distribution. It isn’t always easy to access a virtual environment because its such a large data set.

“I can imagine in the future an improved digital platform. Current 3D platforms are kind of limited in approach. They require you to download everything in one go. We see more of a 3D streaming platform where you have a defined space.”

“If you make it scalable and start digitizing and make it feasible and essentially get in to democratizing, you deliver a stronger sense of cultural understanding between parties. You take people out of their bubble. And somewhere down the line, you get to world peace.”

Images and media courtesy of Reality Virtual.

No Comments