Articles

Editor’s Picks

Think Personalized Learning is New and Innovative? Ask Audrey Watters

By Cait Etherington

April 28, 2018

Personalized learning is a current catchphrase in edtech. While many companies and educational institutions now purport to offer personalized learning, however, what it actually means remains unclear. Is it learning that offers immediate and student-specific feedback? Is it competency-based learning? Is it learning that brings students into the instructional design process?

Journalist and education specialist Audrey Watters, the great mind behind Hack Education and The Monsters of Education Technology series of books, argues that personalized learning is not only a vague and widely misunderstood concept in education but also far from new or innovative. As Watters discussed in a lecture delivered at the CUNY Graduate Center on April 26, personalized learning actually has a very long history, and this history offers key insights into the current personalized learning trend.

Teaching Machines from Pressey to Skinner

When most people think about personalized learning, they recall B.F. Skinner’s teaching machine. Skinner, best known for his ideas on “radical behavioralism,” believed that the behavior of animals and people, especially children, could be modified through certain interventions and repeated exercises. His teaching machine was essentially designed to mechanize his approach to behavioralism. However, a deeper dig into history reveals that Skinner’s 1958 patent for a teaching machine came long after several other earlier inventions.

As Watters has discovered in her extensive research on the history of teaching machines (she is currently writing a book on the subject), the first patent awarded by the U.S. Patent Office for a teaching machine was awarded to H. Chard back in 1809 for a “Mode of Teaching to Read.” In 1810, S. Randall filed a patent an equivalent writing machine. Then, in 1866, Halcyon Skinner filed a patent for an “Apparatus for Teaching Spelling.” Still, the inventor whose machine most closely resembles Skinner’s machine is arguably Sidney Pressey.

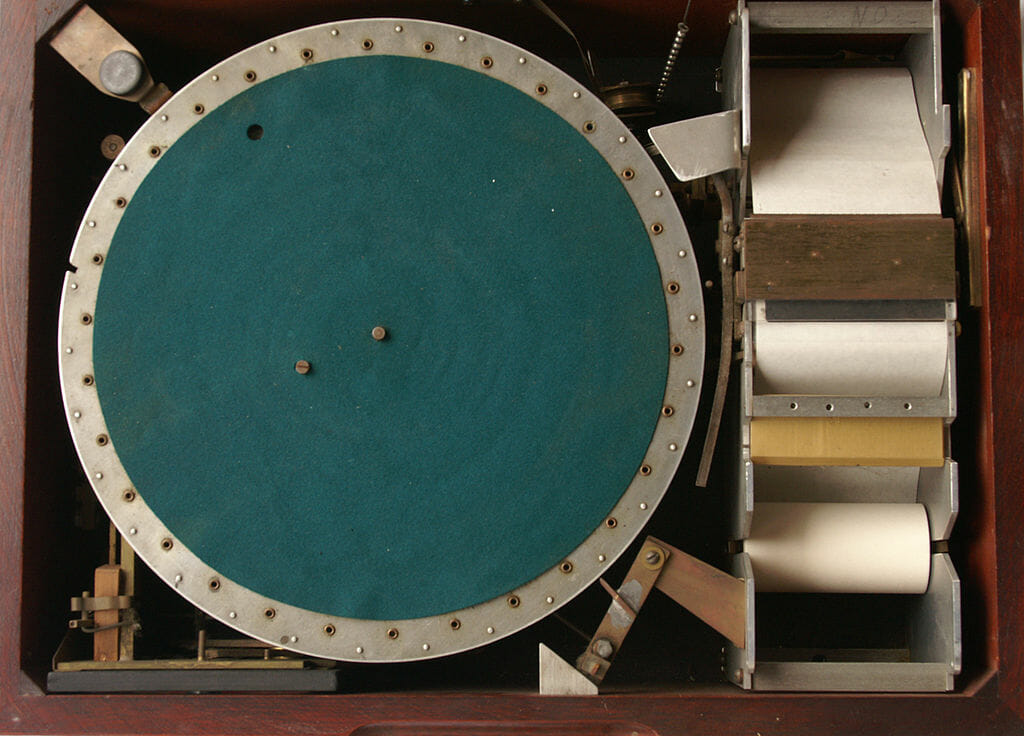

According to Watters, the contemporary teaching machine may, in fact, begin with Pressey rather than Skinner. The Ohio State University psychology professor first displayed his “machine for intelligence testing” at the 1924 meeting of the American Psychological Association and four years later, received a patent for the device. In 1930, Pressey patented a second but related device known as the “machine for intelligence tests.”

According to Watters, the contemporary teaching machine may, in fact, begin with Pressey rather than Skinner. The Ohio State University psychology professor first displayed his “machine for intelligence testing” at the 1924 meeting of the American Psychological Association and four years later, received a patent for the device. In 1930, Pressey patented a second but related device known as the “machine for intelligence tests.”

Pressey’s teaching machine, which looked a bit like a typewriter carriage with a window designed to reveal questions and answers, essentially wanted to speed up the process of giving and grading standardized tests. When a student pressed a key on the Pressey teaching machine, their answer would be recorded. When they completed a test, the tester simply slipped the test sheet back into the machine and took note of the score on the counter. According to Pressey, this would also effectively eliminate the evaluation errors made by teachers. But this is also where the history of teaching machines and personalized learning gets a bit confusing.

The Overlapping Histories of Standardized Testing and Personalized Learning

On the surface, personalized learning appears to emphasize the individual student and their needs, but most early teaching machines designed for personalized learning (e.g., let students move through lessons at their own pace rather than at the pace of the entire class) were in fact also promoting standardized testing. The link is especially apparent when one considers Pressey’s history.

As Watters emphasized in her recent lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center, in addition to developing teaching machines, Pressey was a vocal and active supporter of standardized testing. He also developed and published hundreds of standardized tests. For Pressey, teaching machines were considered essential to standardized testing, since these machines could theoretically ease the grading burden that standardized testing was increasingly placing on teachers.

So, given the history of personalized learning and its curious link to standardized testing, should we trust the grand claims being made by contemporary edtech companies and institutions promoting personalized learning? Is personalized learning just standardized learning by another name? In her talk, Watters stopped short of making this specific claim, but her historical insights certainly do suggest that when one starts to explore the history of teaching machines and personalized learning, they soon discover two histories running parallel.

Watters further observes that in the current educational market, there are other reasons to be cynical. Here, she uses a Netflix analogy. On the one hand, Netflix creates the illusion of personalizing our movie selection by selecting films that reflect our previous picks but in fact, Netflix is really only offering us a small selection (based on the films it currently has available on the site). The same holds true for personalized learning. As Watters notes, a student may be able to select which lesson they complete first and how quickly they move through the material, but in actual fact, the content and evaluation methods remain the same and in some respects, they may even be more rote than many face-to-face based classrooms methods of teaching and learning.

In other words, the “personal” in personalized learning may be less focused on responding to individual needs and more focused on ensuring that every student can be easily ranked, placed, and controlled in the much bigger teaching machine known as the education system.

No Comments