Editor’s Picks

New Study Suggests Availability of Federal Loans Caused Tuition to Skyrocket

By Henry Kronk

January 15, 2018

For the past few years, one fact about college tuition has been clear. It’s not just increasing; it’s skyrocketing at an accelerating rate. While many blame this on forces such as decreased federal subsidies or students who have come to expect a pampered college experience replete with sushi bars and lazy rivers, new research suggests that both theories are misplaced. The study conducted by researchers Grey Gordon of Indiana University and Aaron Hedlund from the University of Missouri finds that the main force behind rising tuition is the amount and the rate at which students are permitted to borrow.

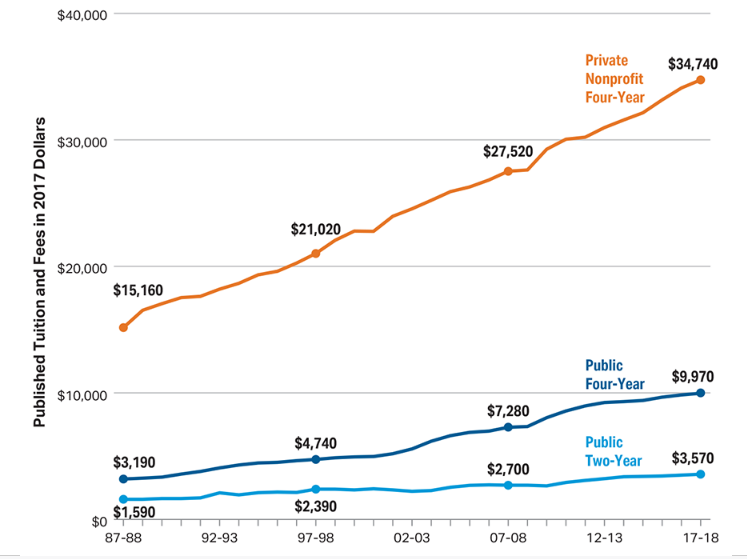

Pinning down the exact amount of college tuition, accounting for federal and state aid, grants, scholarships, and costs of living in a given area can be tricky. Calculating tuition, room, and board, The College Board found that, accounting for inflation, the cost of attending a private non-profit institution doubled between 1988 and 2018, from $15,160 to $34,750. Among public non-profits, it tripled (from $3,190 to $9,970).

Condensing everything down, Gordon and Hedlund put the average sticker price cost of tuition and fees at $6,630 in 1987. In 2010, it stood at $14,510.

With this in mind, administrators, educators, students, and parents have had two questions going through their head in recent years: how did this happen? And what can we do to fix it?

How Did Tuition Spike So High?

Grey and Hedlund asked the first question in “Accounting for the Rise in College Tuition.” The study undertakes a statistical analysis of factors influencing tuition costs between 1987 and 2010.

According to the authors, most arguments take one of two positions which generally follow the logic of supply-side vs. demand(-side) economics. Many voices in the supply-side category (alternatively known as trickle-down economics), are quite loud. These are the arguments that, as states and the federal government withdraw support, tuition rises. Much research indicates that this is certainly a factor, but it does not tell anywhere near the whole story. (Another recent study found that tuition rises only $5 for every $100 in budget cuts.)

According to the authors, most arguments take one of two positions which generally follow the logic of supply-side vs. demand(-side) economics. Many voices in the supply-side category (alternatively known as trickle-down economics), are quite loud. These are the arguments that, as states and the federal government withdraw support, tuition rises. Much research indicates that this is certainly a factor, but it does not tell anywhere near the whole story. (Another recent study found that tuition rises only $5 for every $100 in budget cuts.)

On the demand side lies what is known as the Bennet Hypothesis. This is the belief that financial support and tuition share a positive correlation. In other words, as student aid, grants, and scholarships increase, tuition does as well. Much research both supports and refutes this hypothesis.

After developing a model that could adequately match and predict real data, the researchers were able to manipulate it in order to discover which factors account for specific outcomes. It allowed them to ask “what would have happened if X occurred?”

Demand-Side Plays the Biggest Role

According to the authors, “the demand shocks— which consist mostly of changes in financial aid—account for the lion’s share of the higher tuition. Specifically, with demand shocks alone, equilibrium tuition rises by 91%, almost fully matching the 102% from the benchmark. By contrast, with all factors present except the demand shocks (column 7), net tuition only rises by 14%.”

To state this conclusion baldly, as states and the feds increase financial aid and support, institutions raise their tuition. The Bennet Hypothesis is confirmed. Reagan was right: cutting taxes up top leads to benefits at the bottom.

But that is not the real story. According to the authors, the biggest factor in changing financial aid is the availability of federal loans. “During our period of analysis, annual and aggregate subsidized Stafford loan limits were increased in 1987 and five years later in 1992. The Higher Education Amendments of 1992 also established a program of supplementary unsubsidized Stafford loans and increased the annual PLUS loan limit to the cost of attendance minus aid, thereby eliminating aggregate PLUS loan limits. Interest rates on student loans also fell considerably during the 2000s.”

In other words, it’s not so much that nonprofit educators were weaned off the dole. Instead, students were able to borrow more and more money. As more funds were made available to students, institutions saw an opportunity to squeeze more revenue out of their customers and raise tuition. This also has been seen in for-profit institutions, which take a vast majority of their revenues from federal student loans. It likely explains the massive surge in cheaper and more focused online programs, such as coding bootcamps and microdegrees.

Gordon and Hedland have provided an answer to why tuition has skyrocketed in recent decades. But as to what we should do about it, that answer is less clear.

No Comments