Articles

Editor’s Picks

Interviews

K-12

ASSISTments Has Won Over $25 Million in Grants with Next to No Business Structure or Marketing

By Henry Kronk

November 26, 2019

While many edtech tools and solutions might show promising results in small studies or certain conditions, very few prove effective at scale. That is not the case with ASSISTments. Developed by former teachers Professor Neil and Cristina Heffernan, the free classroom assessment software has been shown to bring about remarkable academic gains. With that proof of efficacy has come over $25 million in grant funding and top marks from the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse. In the past two months, ASSISTments was awarded $8 million from the DoE’s Innovation and Research Program, along with a further $2 million from a private foundation.

The intervention has a simple proposition: learners need to receive feedback faster and more meaningfully. While completing classroom or homework assignments via the ASSISTments web app (which integrates with Google Classroom), students can access hints if they get stuck and receive detailed feedback immediately after they complete the assignment. Teachers, in turn, are informed about where their individual students and collective classes are struggling on the material, and can respond appropriately.

“Fundamentally, I’ve always believed that our schools can get very inefficient,” ASSISTments co-founder Professor Neil Heffernan said over the phone. “Kids need feedback quickly as they’re learning. Let’s say you get assigned your homework. If you’re lucky, you’ll get feedback tomorrow. We just did a survey of 200 teachers, and only like 25% of them said they give feedback within 24 hours. People fail to appreciate how detrimental that is to learning. With that system, you keep making the same mistakes.”

Not Your Everyday Edtech Org

But while ASSISTments has attracted more funding than many developers who get backed by venture capitalists, the organization is not run like most edtech startups. Thought it was first deployed back in 2003, a non-profit foundation to support its work was just initiated this year. Though it has been used by tens of thousands of teachers and students around the world and has been the subject of massive and rigorous efficacy trials, the org just began using some of its funding for marketing in the past few months.

“In one sense, we’re not even off the runway,” Professor Heffernan said. “Khan Academy, Pearson, McGraw Hill—they’re killing me.”

But in another sense, ASSISTments stands above its peers. It has demonstrated a level of efficacy that few other edtech developers have achieved, regardless of their user base. With help from another $3.5 million grant from the DoE’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), SRI Education conducted a large randomized control trial of ASSISTments across the state of Maine. The researchers gained access to ASSISTments data generated by 3,000 different seventh graders across 43 different public schools. The teachers using the software also were trained to use it in advance.

After the trial, the researchers assessed their subjects using the TerraNova standardized tests, among other metrics. It measures K-12 math knowledge on a continuous 1,000 point scale. On average, learners gain 11.66 points per year in 6th through 9th grade. But after the experiment (on average) the treatment group scored 8.84 points higher than the control. This would be similar to a student who began the study at the 50th percentile in their class improving to the 58th percentile by using ASSISTments. That was the average result the software produced.

The SRI Researchers also found ASSISTments allowed teachers to spend more time covering fewer topics at a deeper level. What’s more, the software was found to especially benefit lower-achieving learners. Among learners who scored below the median of their class before the study, the treatment group outperformed the control by an average of 14.35 points.

These results, along with those of other efficacy trials, have helped land ASSISTments one of the top marks from the DoE’s What Works Clearinghouse.

‘Personalized’ Learning?

Some would describe ASSISTments as a platform that allows teachers to ‘personalize’ learning, but Heffernan doesn’t necessarily see it that way.

“I would like to know which thing to give to which kids at what time. And that’s really hard,” Heffernan said. “There are companies out there that actually make it seem as if they know how to personalize. And I, as a scientist, know the emperor has no clothes. We actually know almost nothing about how to personalize learning. I’ve run 100 different randomized control trials and experiments testing this versus that. It’s rare that you find a good way of personalizing.

“I do have one good one. One of my PhD students, Miss Leena Razzaq, and I did a nice little study where we investigated scaffolding questions.”

Razzaq and Heffernan wanted to know if it would be better to give learners a simple ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ mark to students or if it would be better to employ the pedagogical method known as scaffolding. Scaffolding involves providing more support for learners through the assignment in the form of hints, suggestions, and general encouragement. The researchers separated learners into two groups (higher achievers versus lower achievers) and tested both methods.

“It turned out that for high-knowledge kids, it’s better telling them the complete answer once they click okay and say they’re done,” Heffernan said. “They’ll learn faster, they’ll get through more problems that way. But the scaffolding was actually really important for the low-knowledge kids.”

How ASSISTments Came To Be

ASSISTments’ origin story is almost as remarkable as its efficacy. Neil met his wife and ASSISTments co-founder Cristina teaching math in public schools in Baltimore in the early ‘90s. Neil was active in Teach For America, while Cristina had just returned from volunteering in the Peace Corps.

Neil decided he wanted to pursue education technology and enrolled in a PhD program at Carnegie Mellon.

“There were people there who were already working on making what some people call ‘intelligent tutoring systems,’” Heffernan said. “I sometimes call them ‘slightly intelligent tutoring systems,’ but mine were more like ‘dumb tutoring systems.’ They just do what we program them to do. ASSISTments isn’t going to tell you why you feel the way you do about your mother. It just gives students feedback.”

Neil began videotaping effective teachers to get a better idea of what they do that’s effective. Cristina—who was Cristina Lindquist at the time—proved an especially helpful subject. So Neil named his first system Ms. Lindquist.

Cristina also introduced Neil to her brother, who was developing his own dotcom business. He started telling Neil that he should drop the research and come work with him. Neil, who was growing frustrated with his work, eventually agreed to do so.

But then, two weeks before he was set to start his new job, he experienced a seizure. Doctors found a tumor in his brain the size of a ping pong ball.

“I was immediately told, ‘You have two to three years to live. These are the hospice people. You should talk to them,’” Heffernan said.

Heffernan sought a second opinion. The second team confirmed the initial prognosis. Then he walked into the office of Dr. Peter Black at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Black thought he had a chance, and Heffernan took it. The operation was successful, and he began to recover. The experience gave both Neil and Cristina a new perspective on life. They no longer had the urge to join the tech sector—and in the meantime, the dotcom bubble was beginning to burst.

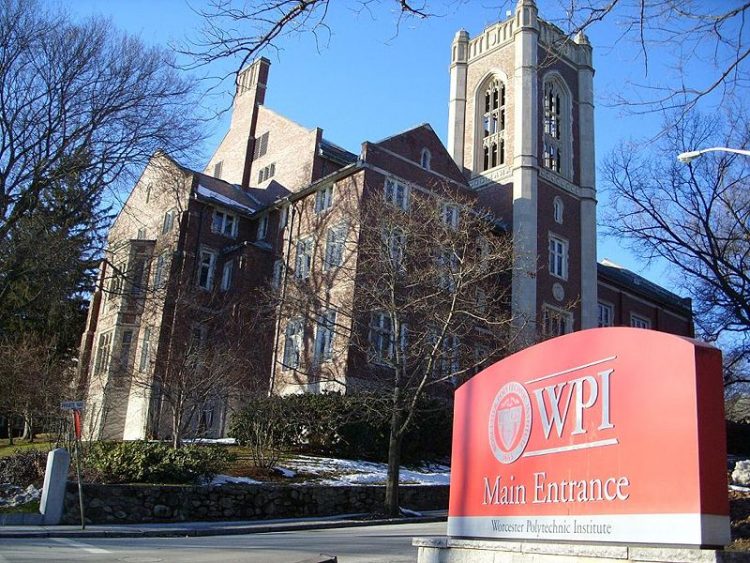

So Neil returned to Carnegie Mellon, completed his PhD, became an assistant professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 2002, and launched ASSISTments in 2004.

Growing from Grassroots

From the beginning, the technology has been available for free. Heffernan has supported its development and deployment almost exclusively through grants from the DoE, the National Science Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and many others. To date, he was earned over $35 million in grant support to continue work on ASSISTments and other projects.

“When I started ASSISTments, I began walking across the street to Forest Grove Middle School and asking the teachers things like, ‘Alright, if a kid screws up this question what are the questions you want to ask?’”

Neil also convinced Cristina to start working with him to develop the platform.

“And then we just did lots of math teacher conferences. Christina will go to the booth and be the booth babe. That’s your term, not mine,” Neil said, turning to Cristina. “To be honest, she does it much better than me.”

Word about ASSISTments has spread almost entirely through word-of-mouth.

“People ask us about how we communicate with districts and principals and stuff,” Cristina said. “Since we’re free and people can just start using the tool, it’s really the teachers that get started using it.”

“I’m such a research geek,” Neil said. “This year, we were pitching funders to do a randomized control trial. And the foundation was like, ‘I think we should fund you just to do some marketing. Because no one knows who you are.’ Cristina was smart enough to kick me under the table and say, ‘Sure, we’ll take your money to do that.’”

Getting the Org Going

There is only one revenue stream outside of grant funding supporting ASSISTments: teacher training. Schools and districts can hire Cristina (and, more recently, a growing team of teacher trainers) to come in and train teachers on how best to put ASSISTments to work.

“Our business sucks,” Heffernan said. “We have like $13 million to spend and I think we’ve collected $30,000 in professional development fees. We don’t really care about making money. But we do know that when some principal or superintendent says, ‘Hey, I want to get going,’ we should have some sort of answer.”

Things have begun to change somewhat. The Heffernans established a 501-C non-profit to support their work this year. They now employ a team of a few dozen professionals and WPI students to further research, take care of product development and support, expand teacher training, and more.

They’ve also been helped along by the growing proliferation of open education resources (OER), which pair naturally with the ASSISTments system.

“It so much easier for a teacher to start going with ASSISTments when they find out, ‘Oh, you guys already have engaged with OER and you get feedback on every question?’ Like they don’t care about our research and that we’re getting better and better over time. They’re just like, ‘Wow, we can use this to give feedback. Wonderful.'”

Neil and Cristina remain committed to using ASSISTments to advance science and make their data sets available to researchers. But that has not come without its own headaches. Some suspect ASSISTments acts as a data mining operation with motivations outside of learning science. Others still are worried about privacy and data security.

“We anonymize all our data sets. But students solved 12 million problems with ASSISTments last year. It’s only going to take one kid to write their social security number in a problem or for somebody to de-anonymize one set for us to get sued.”

But for the Heffernans, continuing the development of ASSISTments remains mostly business as usual.

Featured Image: monkeybusinessimages, iStock.

No Comments