Articles

Editor’s Picks

Interviews

Language Learning Apps Like Babbel Are Popular, But Do They Work? Yale Researchers Investigate.

By Henry Kronk

July 24, 2019

Language learning apps have seen massive uptake in recent years. Duolingo reported it had surpassed the 300 million user mark last year. Other free options like Busuu and Memrise count their users in the tens of millions (Busuu is nearing 100 million). Babbel, which offers subscriptions to its language learning mobile and web app, announced 1 million paying customers in 2016. This popularity speaks for itself. But outside of these figures, user reviews, and personal anecdotes, few know how well these language learning apps work. Babbel has been trying to change that. In recent years, the company has commissioned three efficacy studies into its product, the latest of which was published earlier this month.

The study was conducted by two researchers from the Yale University Center for Language Study, Director Nelleke Van Deusen-Scholl and Associate Director Mary Jo Lubrano.

Van Deusen-Scholl said that, when apps like these began to emerge, she was skeptical about their use and effectiveness.

“I thought, ‘Well, I could be criticizing all of this, but if I want to be fair, I should also take a closer look at it,” Van Deusen-Scholl said.

The Study: “Measuring Babbel’s Efficacy in Developing Oral Proficiency”

The two received data from a sample of 117 participants who were using Babbel to study Spanish. Each learner had either no previous learning experience with the language, or were at least 40 years of age and had not studied Spanish since they were students.

The sample stood out in an academic context in regard to one variable: 75% of participants were over the age of 40.

“In a sense, that created a more ‘real’ sample of people interested in using Babbel,” Van Deusen-Scholl said. “Because if you do a study (and, you know, we could do the same thing here [at Yale]), you’re limited to the students at your institution, you’re going to get a much narrower age range, and you’re going to get students who are already studying. They’re sort of a captive audience, they may or may not already know some of the language, and so on. So it was exciting for us to investigate a very broad cohort that included, surprisingly, a very large number of older individuals.

“Those are usually not people included in research. It’s a population that’s rarely studied and taken into account. That yields all these other kinds of interesting results that get at questions like, ‘What do these apps do?’ ‘Who are they for?’ ‘What use do they have?’”

The sample members’ motivations for learning the language tended to be for travel or mental fitness. Just 15% said that speaking Spanish would help them do their job. Instead, 74% said that they wanted to travel to a Spanish-speaking country.

These learners were then given access to the Babbel Spanish learning modules and set free to learn over a 12 week period.

Learning Spanish with Babbel

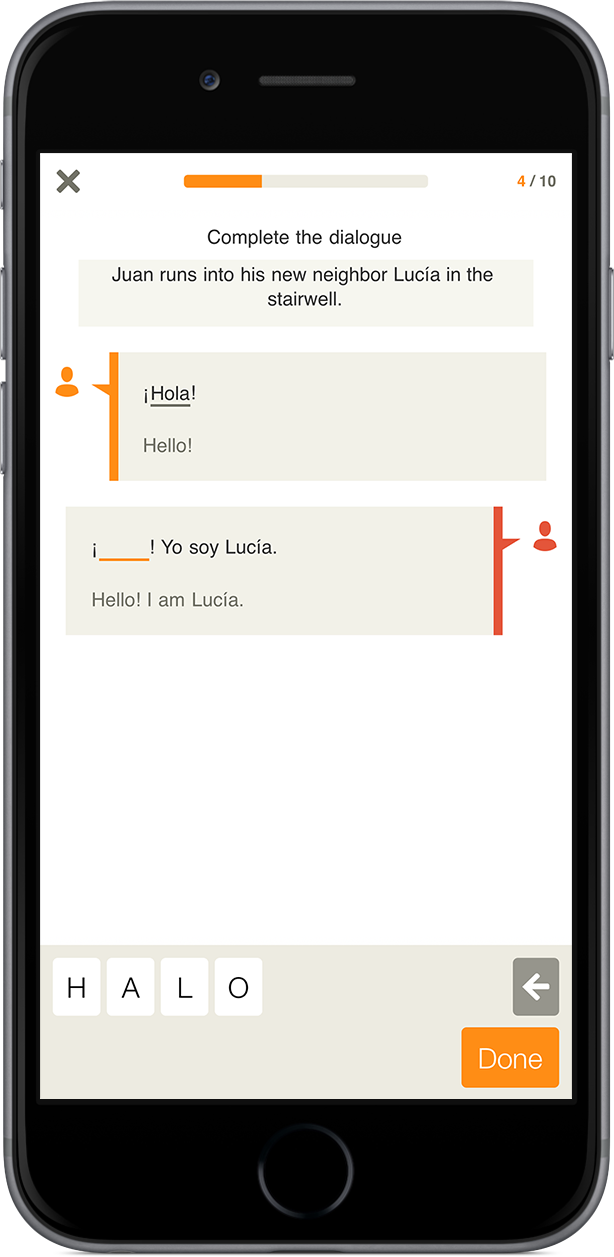

The Babbel language learning app is comprised mostly of short 10-15 minute lessons which focus on every day conversations that language learners are likely to use, like asking for directions, ordering food, and speaking about one’s personal life. It also employs a personalized vocabulary teaching feature, which tracks the words a user knows and retests them at determined periods to employ a ‘spaced repetition’ learning technique. To conduct all of this activity, the app listens to and understands a users’ speech, looking for qualities like correct pronunciation.

Over the course of 12 weeks of study, the average student put in 48 hours on the Babbel app and completed 110 lessons. While many stuck exclusively to the app, others were more enthusiastic and looked to other materials to further their study.

After the 12 week period, learners were then asked to complete the online version of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages’ (ACTFL) Oral Proficiency Interview. The test places speakers on a spectrum that includes the rank of novice, intermediate, advanced, and superior. Each rank is subdivided into categories of low, mid, and high.

Most of the participants in the study unsurprisingly scored in the novice category. 24 of the learners, however, made it into the intermediate level. Of those who scored in the novice level, most (36) were novice mid speakers.

As the authors write, “it was surprising to see such results after a relatively short period of language study, particularly given the lack of personal interaction that is typical for language learning apps. As mentioned earlier, other factors, such as prior experience in learning a related language or using additional resources may have played a role in these results as well.”

In the exit survey, users generally expressed satisfaction with the app, with large majorities said they enjoyed using it, it was well organized, easy to follow, and they could retain what they learned.

Language Learning Apps Stand in their Own Corner of Edtech Tools

As instances of mobile-based and personalized adaptive software, language learning apps stand at a few crossroads in education technology.

In an article in The Atlantic published last December, David Freedman describes his experience with Duolingo. He called his time on the app ‘addictive,’ in part because of the constant notifications, checkpoints, and praise he received from it. (“Finishing a lesson was a full-out digital celebration featuring treasure chests with flapping lids.”)

There is a negative quality to Freedman’s take. But while Babbel doesn’t have these Candy Crush-style features to the same degree, Van Deusen-Scholl said that they can be a good thing.

“With language learning, you want to align the communication strategies and the behaviors with things that they’re already doing in real life,” she said. “If you want to teach a language, you might also want to teach texting in that language. A lot of teachers get a little nervous doing that. But it’s part of the cultural behavior of most groups. I think the reason that there is so much attrition in language learning—online or in-person—is that it’s frustrating! You spend years becoming fluent. So anything you can do to keep learners coming back, that’s what you want to do.”

Adaptive Personalized Language Learning

These language learning apps also operate without an instructor. They regularly assess learners’ progress, and tailor instruction based on their ability using artificial intelligence functions. As such, they use a technology-based personalized adaptive learning style of teaching.

Proponents of the pedagogy say that the ideal environment for a learner to learn is one-on-one with a teacher—at least for imparting educational content. But Lubrano and Van Deusen-Scholl say this isn’t so much the case with language learning.

“I think we’ve moved away from the model of filling up a bottle with words and wisdom,” Lubrano said. “The instructor now is a facilitator, and he facilitates that learning. But for that to happen, there need to be multiple learners who share that motivation in an environment that enables them to practice.”

“In language learning, interactions are crucial. Interaction requires people to interact with,” said Van Deusen-Scholl. “Now, you can do that in a classroom with multiple learners. Ideally you want to be in the environment where the target language is spoken so you can talk to native speakers. So human-app or interface interaction is by no means ideal. It’s another way that you can try to mimic the conditions. But it’s still a very difficult thing, and I think that’s one of the reasons we were initially skeptical about being able to actually measure proficiency with people using an app because it does not have that interactive component.

“We found that to get people to a very basic level of competency and proficiency, it works. After that, you need to go out and meet other speakers.”

Featured Image: Alessia Cocconi, Unsplash.

No Comments