Articles

Editor’s Picks

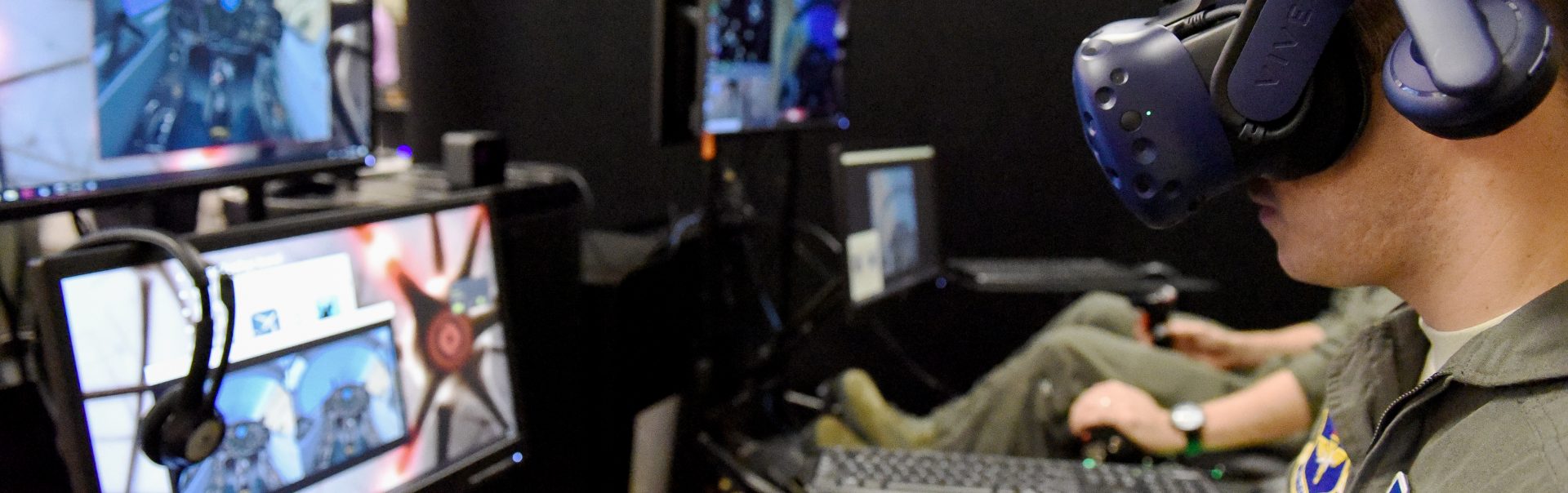

VR in Post-Secondary Education and Skill Training: What Academics Know

By Henry Kronk

August 15, 2019

VR headsets as we know them today have been around for just over six years. Educators and instructors have begun to use them for a wide variety of functions and applications. Following this trend, more and more academics have begun to investigate their uses. A review of this literature was recently published by researchers from the University of Alberta, Edmonton. “Head-Mounted Display Virtual Reality in Post-Secondary Education and Skill Training,” by Brendan Concannon, Professor Shaniff Esmail, and Associate Professor Mary Roduta Roberts was published in Frontiers in Education on August 14. Their findings provide a panoramic view of the VR post-secondary education and skill-training landscape.

The review identified 119 relevant academic reports and 38 experiments. Of these, 35 were found to bring about positive outcomes of some kind. But as will be seen, the incentives, applications, and effects of each VR educational application varied widely.

VR in Post-Secondary Education and Skill Training from 2013 to the Present

Following a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2012 that raised nearly $2.5 million from roughly 10,000 funders, the Oculus Rift was brought to market in March of 2013. The headset launched a new generation of head-mounted display virtual reality (VR) devices. These VR viewers and consoles have been put to various uses, and education forms just a slice of that pie. Within educational applications of VR, their uses for skill-training and post-secondary education are even narrower.

Because of this development, the researchers decided to confine their search to the period between 2013 and the present. In their conclusion, they acknowledge that some relevant principles, findings, or theories regarding education and VR might be available from before 2013. But they justify their decision with the rapid advancement in VR technology during the early 2010s that changed the game.

Solving the Latency Issue

By some definitions, head-mounted VR dates to the 1950s. VR technology in the 90s and 2000s could both present a virtual environment and respond to users’ movements in order to create the sensation of inhabiting a virtual space. But latency between sensing users’ movements and the display tended to shatter the suspension of disbelief and made VR experiences less effective. That changed with the Oculus Rift and other models.

The authors identify three general qualities that typify current VR experiences: immersion, interactivity, and imagination. While those first two are fairly straightforward, the researchers describe the imaginative quality of VR as “the extent of belief a user feels is within a virtual environment, despite knowing he or she is physically situated in another environment.”

Others have described VR environments as those that bestow a sense of presence to the user. That presence is highly subjective, but some have theorized that it has physical, functional, and psychological dimensions.

The authors stress that, while these qualities are often at work in VR experiences, they need not all be present or working to the same degree.

How Much Has VR Been Studied?

The authors conducted two searches of a variety of databases with numerous different keywords. The first occurred in October 2017, when 874 reports were initially identified. After a vetting process, which involved removing duplicates and other measures, 58 made the cut.

A second pass was conducted in January 2019. With this second pass, another 61 reports were added, bringing the number of total reports to 119. The authors note that this marks a “105.17% increase in eligible immersive VR literature in post-secondary education in the span of 15-months.” While it forms just two points in time, these findings indicate that research of VR in post-secondary and skill training has been accelerating rapidly, to say the least.

Most of these VR teaching tools were put to use in the fields of science and technology (52), followed by health sciences (49). Next came arts and humanities (16), military and aerospace (3), and various (4). Within each field, applications tended to vary widely.

Of the reports identified, 38 involved original research and experiments. Most compared the use of VR to other media, like laptop or desktop screens or mobile devices. Of these, 35 reported positive results in some way, with “13 showing an increase in user skill or knowledge, 10 showing an increase in user engagement or enjoyment, 8 stating immersive VR had some form of extra capability over traditional methods, and 4 stating both an increase in user skill and engagement.”

Why Was VR Used?

VR has legitimately been found to increase user engagement and interest. In other words, learners tend to get more excited about subject matter when engaging with it in VR. But the technology also has many other concrete advantages. The authors of the survey identified these as:

- Skill Training: VR allows users to practice specific skills virtually. For example, the authors identify the military house-clearing simulation, like the 2016 title Hot Dogs, Horseshoes, and Hand Grenades.

- Convenience: The convenience factor of VR applies to both time, location, and resources. For remote students, it can be easier to engage in VR training than traveling to another location to do so. It can also be less expensive than some training and involve less time.

- Engagement: 10 of the 38 experiments identified found that the technology increased user engagement.

- Safety: Donning a VR headset is obviously safer than many hazardous scenarios that people need to train for. But the authors distinguish this category further, writing, “A virtual environment that focused on safety may have included some or all of the following: (a) The practice of awareness skills necessary to reduce the probability of accidents occurring, (b) The practice of technical or non-technical skills necessary to handle an abnormal operating condition, (c) The ability to interact with virtual objects that would be deemed too dangerous in the real world.”

- Highlighting: This function of VR draws learners’ attention to specific aspects of their environment.

- Interactivity: VR environments are interactive by virtue of the fact that the display will respond to the motion of users’ heads. Many, however, go far beyond this with the addition and use of hand controllers.

- Team Building: Some teams need to be able to work together in specific situations. Others simply need to break down interpersonal barriers and operate more cohesively as a group to overcome challenges. The authors identified VR simulations that addressed both needs.

- Suggestion: The final role of VR identified by the authors, suggestion, involves influencing behavior. This can come in a few different forms, like sensitivity training, experiencing other perspectives, or encouraging enthusiasm. For example: the New York City Police Department developed a VR intervention to increase understanding between the force and the community.

The authors conclude with a long discussion of ‘curricular recommendations’ made by the various reports they discussed, along with detailed considerations to take into account. There is obviously much work still to do in the field of VR in post-secondary education and skill training. But the base of knowledge surrounding the technology has begun to be established.

Read the full report here.

Featured Image: John Ingle, U.S. Air Force.

[…] growing demand of online support post-pandemic, audiences have looked to notable conglomerates like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon for edtech resources. Smaller companies, like Development Experts, have taken a […]