Our recent annual study of student reading habits found that digital reading doubled in 2020, but will the trend continue, or is it an artifact of remote learning during a pandemic?

For more than a decade, Renaissance has published the What Kids Are Reading report to help educators guide students to books they will love. Based on a sample of more than 7 million students across 26,000 schools in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, the report is one of the largest survey of student reading habits in the world.

Before I share some of the key findings of What Kids Are Reading, it is worth taking a moment to answer the question: “Why does it matter what kids are reading outside of classwork?”

There’s No Substitute for Independent Reading

Educators have known for years that students who read a lot outside of school perform well academically, and there is an emerging body of research that’s beginning to explain why. At the simplest level, as students read more, they gain the ability to recognize more words instantly, which leads to more fluent reading. But it continues to build from there. Each book provides more vocabulary, more background knowledge, and even sharper critical thinking skills.

An anecdote will illustrate this effect: a colleague recently told me about the first time she saw the word “façade.” She had only heard it before and had assumed it would start with a “ph,” like “phalanx” or “pharaoh.” Of course, it starts with an “f,” so when she saw the word for the first time, she had to sound it out and decode it. Each time she saw it after that, it got easier and faster for her to recognize the word.

7 million students. 255 million books. Explore the world’s largest annual study of K–12 student reading habits: https://t.co/CRD9QHmgYQ pic.twitter.com/iUO0TKQ96E

— Renaissance Learning US (@RenLearnUS) April 5, 2021

In cognitive science, researchers refer to this ability to recognize known words almost instantly as having strong “orthographic representations.” The impact on reading comprehension is significant. When readers have strong orthographic representations, they use less of their brains’ processing power for decoding words, which leaves more capacity for actually comprehending what they are reading. And the only way to build such representations is through reading.

Additionally, as students encounter words more often, and used in different ways with alternative definitions, they can acquire vocabulary faster than they can via classroom instruction. Using the example from above, they can come to understand that “façade” may mean some kind of false front or an attempt to hide an unpleasant situation.

Members of the cognitive science community are beginning to push back on approaches that “over-skillify” reading, such as extensive practice with isolated skills like finding the main idea. While discrete skills and reading strategies represent some aspects of reading and do offer some benefit to students, true comprehension involves the integration of many skills, as well as vocabulary and background knowledge. They must all be practiced together. Focusing on individual strategies has a ceiling of effectiveness, but building vocabulary and knowledge does not.

Last year, for example, the Fordham Institute published a report finding that, between struggling readers who received extra time in social studies and those who received extra time in reading skills, the students with extra social studies time made better reading progress. Practicing reading skills will never teach students that the Berlin Wall was anything other than a wall in Berlin, but reading in a social studies class very well might.

What Are Kids Reading This Year?

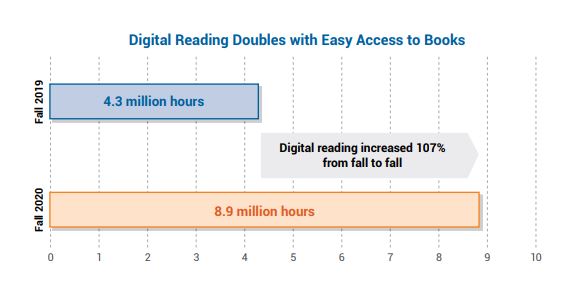

People really needed some good news this year, and I am fortunate enough to have some positive findings to deliver from this year’s report. The first bit of good news is that digital reading increased 107% from year to year, with students finishing some 255 million books.

The other piece of good news is that students are still reading at the same difficulty level and comprehending just as much as in previous years. This year’s fifth graders, for example, are reading texts just as difficult as last year’s fifth graders, and they are comprehending what they are reading at a similar level, despite experiencing greater disruption to their learning than at any time in recent memory.

The Future of Student Reading Practice

The shift to distance learning may have caused an artificial boost in digital reading in this year’s report, but there’s still reason to believe that the future of student reading is going to be a lot more digital. For one thing, it is a trend that we have observed previously, albeit with a less dramatic year-over-year rise.

Digital reading also improves access to books for students in a fundamental way. The other day I was talking with Judi Paul, the now-retired founder of Renaissance. She told me about how, when she started back in the 1980s, she was struck by how many teachers called her and asked where to get books. That was before Amazon and digital reading—even before the big bookstores like Borders and Barnes & Noble had taken off. There was probably a library in town and some small bookstores, but they were generally pretty limited in what they offered.

Of course, students and teachers have much better access to books today, even without digital reading platforms, but even going to the school library presents hurdles to access that students simply do not encounter with an e-reader. They do not need to get a hall pass, walk to the library, figure out how to navigate a card catalogue—or run the risk that when they do all this, they will find the book checked out and their time wasted. With a digital book, they have what they are interested in learning about in just a few clicks, right in the moment that they are engaged and interested in that topic.

We are a long way from the pre-Amazon world of the 1980s, but we’re still in the middle of the shift to digital reading.

Increased reading of nonfiction is likely to continue as well. That is also a trend that has been consistent across several years of What Kids Are Reading and, as more states lean into the emphasis on reading nonfiction, I expect to see that trend continue.

As a final point, I think we will see more books related to diversity and inclusion in the coming years. Educators are looking for texts that will help their students understand some of the really complex and difficult questions they are dealing with in the world. As a white man in contemporary America, there are some experiences that I can never fully understand, but when I read books about people who do have those different perspectives, I can gain a little insight into what it is like to be someone else. Each book I read about people who are not quite like me is another opportunity to walk around in someone else’s shoes and learn to empathize with them a bit.

Dr. Gene Kerns (@GeneKerns) is vice president and chief academic officer at Renaissance. He is a third-generation educator and has served as a public-school teacher, adjunct faculty member, professional development trainer, district supervisor of academic services, and academic advisor at one of the nation’s top edtech companies. He has trained and consulted internationally and is the co-author of three books. He can be reached at [email protected].

Dr. Gene Kerns (@GeneKerns) is vice president and chief academic officer at Renaissance. He is a third-generation educator and has served as a public-school teacher, adjunct faculty member, professional development trainer, district supervisor of academic services, and academic advisor at one of the nation’s top edtech companies. He has trained and consulted internationally and is the co-author of three books. He can be reached at [email protected].

Featured Image: Perfecto Capucine, Unsplash.

One Comment