Articles

Editor’s Picks

eLearning Supports a University for Refugees in Italy

By Cait Etherington

June 16, 2017

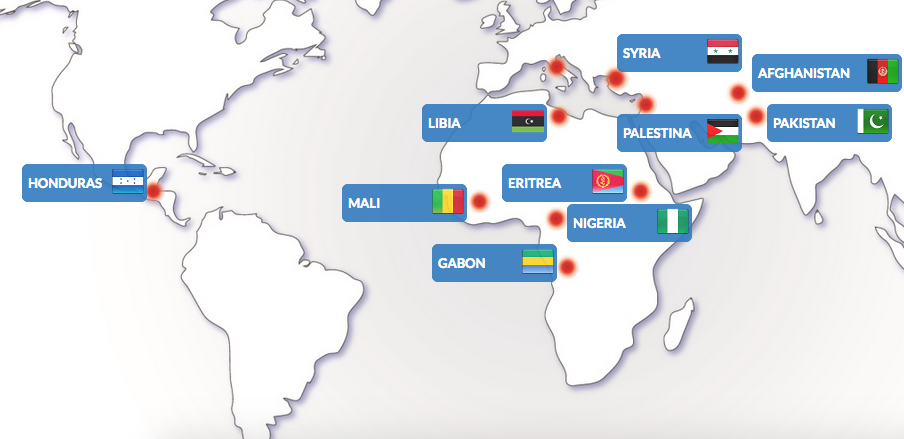

In 2015, 153,842 asylum seekers arrived in Italy. Today, the flood of migrants continues. Most come by boat and arrive with little or nothing. Many of the asylum seekers are also young people who have left university to flee war or economic instability in countries such as Syria, as well as other countries throughout the Middle East and North Africa. In 2015, nearly 84,000 of Italy’s asylum seekers indicated upon arrival that they were seeking to further their education. For Italy, this has created a pressing educational emergency but also given rise to a university for refugees.

On June 15, Nicola Paravati, who directs International Affairs at the Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO in Italy, was in New York to delivered a talk at the International Conference on E-Learning in the Workplace. In the talk, Paravati shared how one Italian university is responding to the migrant crisis and its related demand for education not only in Italy but in refugee camps around the world.

Education without Boundaries

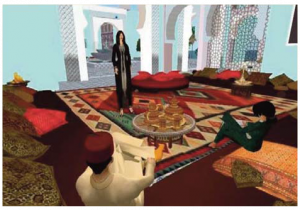

UNESCO’s 2030 goal for education is “lifelong learning opportunities for all.” The Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO has taken this mission to heart and is pursuing the realization of this mission in its “education without boundaries” project. The project’s history and mandate are stated on the university’s website and emphasize a commitment to teaching in many language, including English, French, Italian, Greek, and Arabic, and welcoming students from 140 different countries. Notably, in addition to using video conferencing and interactive online learning tools, the International Telematic University UNINETTUNO deploys 3D tools, including Second Life, to bring students together in virtual classroom settings.

Returning to the University’s Multilingual and Multicultural Roots

As Paravati emphasized in his ICELW talk, the roots of the university (notably, Italy is home to the second oldest university in the world) were multilingual and multicultural. In the middle ages, students came together to study in Arabic, Greek and Latin and professors and students alike were often highly mobile, traveling from country to country to seek out the very best scholars. Paravat emphasizes that in many respects, UNINETTUNO is returning to the roots of the university. At their inception, after all, most universities did operate in multiple languages. Notably, Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO currently has 15,000 student in 140 countries and offers 25 bachelor of arts programs, as well as master’s and doctoral degrees.

As Paravati emphasized in his ICELW talk, the roots of the university (notably, Italy is home to the second oldest university in the world) were multilingual and multicultural. In the middle ages, students came together to study in Arabic, Greek and Latin and professors and students alike were often highly mobile, traveling from country to country to seek out the very best scholars. Paravat emphasizes that in many respects, UNINETTUNO is returning to the roots of the university. At their inception, after all, most universities did operate in multiple languages. Notably, Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO currently has 15,000 student in 140 countries and offers 25 bachelor of arts programs, as well as master’s and doctoral degrees.

Accreditation of a University for Refugees

One challenge Italy currently faces (and the same holds true in other European nations processing high volumes of migrants) is accreditation. As Paravati noted, “We don’t always have an equivalent diploma or degree, so determining a asylum seeker’s level of education can be very difficult.” To ensure that the asylum seekers’ levels of education and and certifications in professional fields are recognized, the Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO has found experts around the world to help carry out detailed assessments of students’ previous levels of educational obtainment and experiences. In some cases, a test is also given to help establish a newcomers’ level of education. However, it is never assumed that a student must start their education from scratch. Indeed, the Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO has already placed several migrants in master’s level programs. The fact that the University for Refugees partners with the centers where migrants are processed means that educational assessments increasingly take place within days of a migrant arriving in Italy.

Bringing Professors and Students Back Together Online

With the displacement of young people, many professors have also been displaced. For this reason, Italy’s Università Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO is also actively looking to find and hire displaced faculty members from war torn and economically destabilized nations. Paravati reported that in one case, his program was even able to put a young engineering student who is now living in a refugee camp in Lebanon into a course taught by a professor from his former university’s engineering department. “This is important,” Paravati observed, “Because bringing these students and professors together and back together also builds community.”

Funding the Initiative

Despite UNESCO’s commitment to making education accessible around the globe and the availability of funding for related initiatives, Paravati noted that securing funding remains a challenge. “We currently have 50 students with full scholarships, but over 200 applied,” he said, “And more are interested. Funding is an urgent need, and we are exploring options.”

No Comments