Articles

Editor’s Picks

Interviews

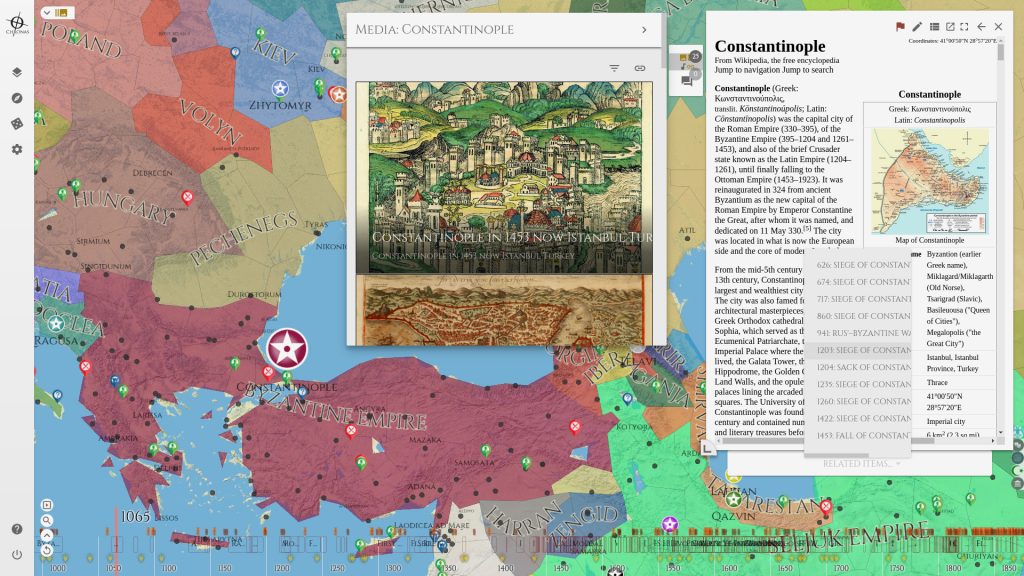

Chronas, with Over 50 Million Data Points, Provides a Map of History

By Henry Kronk

April 09, 2019

Around five years ago, full stack developer Dietmar Aumann was perusing the internet looking for a sort of historical Google Maps. A fan of history, he wanted a map that also had a time slider that could bring him back and show him the former borders of countries, sites of important events, and other information. After finding that such a map did not exist, he did what any developer might do: he built one himself. Chronas.org is the fruit of Aumann’s labors (and a successful Kickstarter campaign). Not only does it show the changing borders of political entities over time, it also includes population, the dominant culture and religion of a given area, migration, notable events, centers of power, and much more. In all, Chronas contains over 50 million data points.

“You know Charlemagne … if you go to German schools, you call him Karl der Große,” Aumann said. “I only made the connection later that the outside world calls him Charlemagne. He was actually a German. He spoke the German language of the time. He was a Frank, which was a German tribe. But now, because he’s called Charlemagne, many think he was a Gaul, that he was French.

“In most schools that you go to, history class is really centered on the country where you study. In the U.S., I guess you learn a lot about the Civil War and the founding fathers. In Germany, you spend most of your time in the Second World War era. In China, or Saudi Arabia, you have completely different topics of focus. The sad thing is that you don’t get that bigger picture.

“When I grew up and started getting a little more interested in history, I never connected how the Ottoman Empire basically links the Medieval Era to the Modern Era. That force that defeated the Byzantine Empire were latter allies with Germany during World War I. Everything is connected. I wanted to show that.

How Chronas Got Started

“My background is not in history. I wanted to study history at one time, but I went to my second preference, which was computer science. I went to university in Bielefeld, Germany, and then Helsinki, Finland and graduated with a computer science degree.

“In 2015 or so, I was working in Belgium. I was looking for some kind of application like Google Maps where you could also have a time slider where you can track back, maybe 500 years or so and you could track how the borders and political entities looked at that point in time. I couldn’t find anything so I thought I’ll try to do that myself.

“By the end of 2015, I had the first prototype of Chronas. It was based on older technology. If you go to Chronas today, it’s based in WebGl, which utilizes the graphics card of the device you’re on. Previous sites didn’t use it at all because internet browsers didn’t support it.

“It only really came into mainstream use in the last couple of years. Because all the bigger browsers started supporting it, I decided to transfer the application. Now it runs very nicely on desktops. Obviously, it depends on the graphics card you have. Now, you can look at hundreds of thousands of markers on a single screen.

“I also included a clustering algorithm, you can toggle clusters of markers. Actually I don’t think it’s necessary on modern systems. My hope is that, as time goes on, graphics cards and machines will only get better and better, and Chronas will be more usable for more people. Right now, it’s still quite heavy for older laptops, mobile devices, and tablets. With time, hopefully that will change.”

As Aumann tells it, Chronas came together slowly over time.

“My first idea was to have a map, to have a time slider, and then see how the country’s borders changed,” he said. “Once I got to that point, I thought it would also be nice to see markers of historic battles or historic people who lived at that time. So I looked at the database behind Wikipedia. I used Wikidata to populate my database with all of the geotagged articles they have (geotagged meaning they have a latitude and longitude assigned to that article).

“Because it’s also a historic map, a point in time was also necessary. So, for example, on Wikipedia, if you look at an old article, like Charlemagne, when you go to an article, on the left, there’s also a link to the Wikidata on the left. If you click that, you can see all that metadata that’s linked or added to that article. With most articles that are popular, they also have latitude and longitude assigned. For example, Aachen, where Charlemagne was born. They also have a point in time—in that case, date of birth and date of death. You can use those data points to map it on the application.

“Wikipedia has a lot more data stored than what you see when you visit an article. And a lot of metadata is added through WikiData, and it’s really easy to use. I don’t use Wikidata directly. I migrated it all to the Chronas database. Now, whenever data is requested by the application, it’s dynamically queried from the Chronas databse.

“Once I had the old prototype done, and I made the decision to upgrade it, I made a Kickstarter campaign. I just wanted to see if people would be interested in it.”

The campaign concluded in June 2017.

The Second Version … With More to Come

“The Kickstarter campaign was successful, I started working on it. As I went along, I thought, ‘Why not add more media to it?’ Like images, videos, podcasts, and link to specific articles? So if you click on certain articles on Chronas, you can also watch or view the different media attached to that article. You can also link other articles. You can jump from one to the next. You can also ask questions—there is a small forum attached to it.

“My idea in that was for people to just get lost in history and go from one to the next and discover connections which they weren’t aware of before.”

Aumann is particularly proud of the migration feature on Chronas.

“When you open the layers menu, a left side bar will appear,” he said. “Then you have area, you markers, you have epics, and you also have migration.”

Click on the feature and, depending on the year you are in, tens, hundreds, or thousands of small arrows will appear on the map, shooting off in all different directions. Each arrow represents a notable person. They originate in the city where the person was born and end in the city where they died.

“You can see the centers of power during a given time,” Aumann said. “They’re basically the cities where most people migrated towards. Those are marked as green. If the circle or the radius grows, more people migrated there. If it’s red, that means people left that place during that time. That feature is available for over 2000 years.

“During the Roman Empire, you can go to Rome and see it’s very important, obviously. You can go to China and see what the capital cities are at that time—the real capital cities. When you go to the 18th century, you can see which people migrated to the U.S., and so on. It was another feature that I thought I should add.”

As one might imagine, Wikidata is far from complete. Aumann, therefore, wanted to allow users to edit the data.

“In the new version, all the data you can see, it’s really easy to add it,” he said. “If you see any problem with any data point, most users will be able to change it. You just need to click on the edit button and then you are directed to a form with all the underlying data. If you, for example, see a person was born in one city and you know he was born in another, you can change the location. Or if you see this guy was inaccurately flagged as born in 1st century, but actually he was born in the 14th, you can change that.

“All those data points then change that migration feature. If you change a person, it will change one small arrow. It’s not baked in, it’s all dynamic.

“History is infinite, and you can make an app to start to represent that. But if you don’t have people who work on that data, edit it, and curate it, you won’t really be able to achieve what you want to do.

“If you have money, maybe you can pay people to do it. But even now, in Chronas, there are over 50 million data points. [And with paying people] you will run into problems. That’s why I wanted to the new version to be editable by the community, just like Wikipedia.

“We can only work with what we have. There will be inconsistencies, that’s not a question. I know when I went to school, Wikipedia could never be used as a source. As a student, what you did was go to Wikipedia, look at those sources, and then link those.

“As a source, Wikipedia is much better than its reputation in 2019. In 2014, I think there were many more problems with it. But now the community has such a robust fault tolerance … If you change something now, a lot of flags go off, which will alert a lot of people to look into what you just changed. They have a really strong revisioning system. The same goes for Chronas.

“When I created it, I knew that people would probably try to vandalize the data and draw their fantasy map. So I implemented a similar revisioning system. If a user is trying to have fun with the map, you can easily report all the changes they made, and they will revert back to the data set.

“Also, every little change you do is recorded. I often look at the revisions and what changes people made. A really common thing people change is whether it should be called the Byzantine Empire or the Eastern Roman Empire. It’s a matter of definition, and that’s why I added a forum where people can discuss those matters and make their argument for one or the other. There is also a voting system where people can elect which one they like.”

Plans for the Future

Aumann plans to keep a version of Chronas online, open, and available to the growing community (there are currently over 6,000 registered users). But he also is considering a few monetization plans.

“We are currently working on a better version where I want to prove what is possible and also see whether people are interested in it. In my view, there should always be available for users to freely add and edit data, just like Wikipedia. Wikipedia wouldn’t work if it were behind a paywall. Similar to that, I would love to have an engaged community who curates the data, adds to it, and makes feature requests. That’s one business model.

“The other one is a separate version of Chronas could also be used for institutional use or online learning tools, which they comes into the area of edtech. I am currently working on a project where a teacher could, if he’s preparing a history lesson, could select a bunch of articles to bring up in class. He could then have only those articles available in Chronas. He could also select the time range. If it’s only relevant in the 19th century, he could lock that time range. He could even lock the viewpoint of the map where he wants his student to focus. Then he could create a collection of articles he wants to show. He could even create his own article with a basic geotagged HTML page. He could then create a quiz to verify his students went through that material. He could even make a quiz after each article. And then, once he is done, he saves it, and then creates a link that he can send to his students.”

Media courtesy of Chronas.

[…] på får kids uppleva nåt annat”, säger Megan Rierdon, specialpedagog på skola i Milwaukee. Megan har på sin skola börjat att använda sig av VR för upplevelser. Barnen får en rundtur i växthuset. “När skolors budgets tightas åt så gäller det […]

[…] At the 53rd St. School in Milwaukee, special needs educator Megan Rierdon could not take her students on field trips with the rest of the school. However, using VR headsets, she was able to give her students the same experiences their peers were having, according to eLearning Inside. […]

[…] they had acquired Texas-based software company SuccessEd in a bid to expand their reach further innovate special educational services for the K-12 community. Details of the deal were not […]