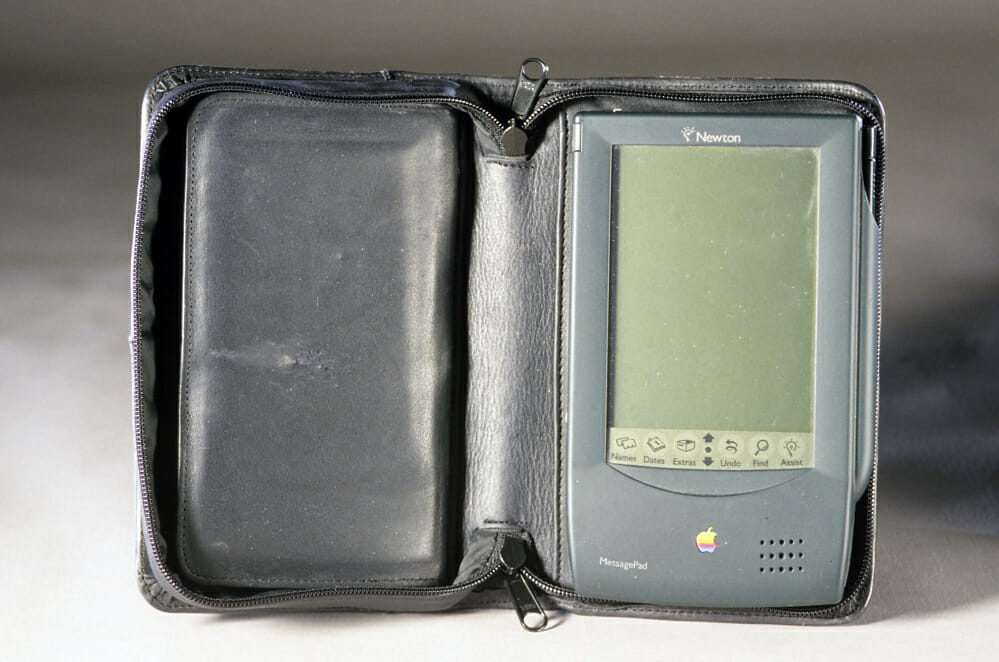

Twenty years ago today, Apple announced that it would no longer produce the Newton. What was the Newton? For those who don’t remember, the Newton was the not-so-distance ancestor of today’s iPads and iPhones. At the time, however, the Newton was simply described as a “personal digital assistant” or PDA. While Newton enthusiasts decried its death, in many respects, the end was just the beginning. While relatively short-lived, the Newton paved the way for both mobile devices and the rise of mobile learning.

What Was the Apple Newton?

A 2013 article in WIRED, aptly described the Newton as follows: “By modern standards, it was pretty basic.” But for the time, the Newton was innovative. It could double as a fax machine and with its stylus, it could even translate handwriting like many contemporary tablets. But as the author of the article, Mat Honan, adds, aspects of the Newton still reflect today’s digital mobile solutions. Years later, there is even a Newton Museum.

So, why was the Newton canceled? There were likely two factors that killed the Newton. First, it was pricey. Naturally, at the time, replacing your notepad or paper calendar, which would likely cost only $10 combined, with a $700 portable computing device was a hard sell. Second, Steve Jobs reportedly hated the Newton.

The Newton Legacy

While the Newton quickly drifted into obscurity, it did not entirely disappear. The device was driven by a 20 megahertz ARM 610 processor with 630 kilobytes of RAM and somewhat shockingly, it was powered by four AAA batteries (yes, like the ones you might pop into a small flashlight or toy). While we’re no longer popping AAA batteries into our mobile devices, the Newton’s ARM processor, in fact, continues to play a key role in mobile computing.

The Newton’s real legacy, however, was the conceptual leap it helped to enact. The history of technology is replete with intermediary steps–moments of transition when old and emerging technologies merge–and the Newton was one of those moments. For the first time, we were given a device that we could carry with us and that had the capacity to do many things. You could use your Newton to look up your contacts, keep track of meetings, takes notes, or do basic math calculations. The Newton, in a sense, was significant because it prepared us for the development of the multi-use devices that now define our everyday lives. While we now take for granted the fact that a phone is also a calendar, camera, video camera, and way to access the web, back in 1991, the idea that one small portable device might do multiple things was still new and revolutionary. The Newton pried open our imaginations and provided some of the hardware needed to set digital mobility in motion.

From the PDA to the eMate

While Newton PDAs were not initially designed for mobile learning, on October 28, 1996, Apple rolled out the eMate, which was one of Newton’s many product lines. As Mike Lorion, at the time vice president of education for Apple Americas, explained on the occasion of the eMate’s release that the device offers a distributed learning environment and in many respects, it serves to extend the classroom. Lorion further emphasized that while making the eMate 300, educators were consulted along the way. As Apple’s press release for the eMate noted, with the eMate, students can now “do most of their critical work wherever they happen to be” and it won’t matter whether they are in a lab, at home, or on the run.

While we are no longer talking about the “distributed learning environment concept,” in many respects, the eMate, one of Newton’s many offspring, represented the first step toward what we now call mobile learning. Combined with the Newton’s broader impact on mobile communications, the Newton undoubtedly played a key role in mobile learning history and more broadly, personal computing and communications.

No Comments