Alarming reports on the increasing rates of screen time and its negative effects have captivated American readers over the past few years. Like cancer-causing cell phone signals or BPA plastic, screens are everywhere and used every day by almost everyone. According to a few thought leaders, they’re also bad. Really bad. Some critics argue that screens even lead to obesity, aggression, teen suicide ideation, and more. Unfortunately, the research supporting these claims suffers from dilution. The category ‘screen time’ is so broad that it can’t possibly lead to many useful findings, if any.

Correlation vs. Causation in Screen Time Research

A recent study that received a good deal of exposure defined screen time for children as “television, videotapes, digital video disc, game devices, computer, cell phone, smartphone, tablet, electronic reader, and child’s learning devices.”

Speaking with Vox, Stanford Psychology Department Chair Anthony Wagner said, “The literature is a wreck. Is there anything that tells us there’s a causal link? That our media use behavior is actually altering our cognition and underlying neurological function or neurobiological processes? The answer is we have no idea. There’s no data.”

In other words, most studies report correlation, not causation. To highlight this, eLearning Inside got in touch with Daniel Je, a content specialist at OneClass who recently conducted his own experiment.

Research from OneClass by Daniel Je

“Our audience is made up of students, so I wanted to see how screen time would affect students’ grades,” Je said.

“I created a very quick survey. I wanted to make it as easy as possible. It asked how many hours per day people were using their phone on average over the last seven days. I wanted to see if that had an impact on their grades. I then asked for their letter grades in school for their cumulative GPA.”

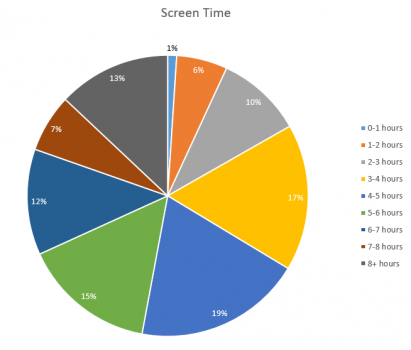

In the end, 875 1st year undergrads answered Je’s survey.

“I kind of expected that the more students used their phones, the lower their letter grade would be. But looking at the data as it came in just on the surface level, I compared the averages of students grades who spent 7+ hours on their phone a day with students who spent 1-2 hours per day. The averages were actually very similar in terms of their letter grades. That’s something that threw me off.

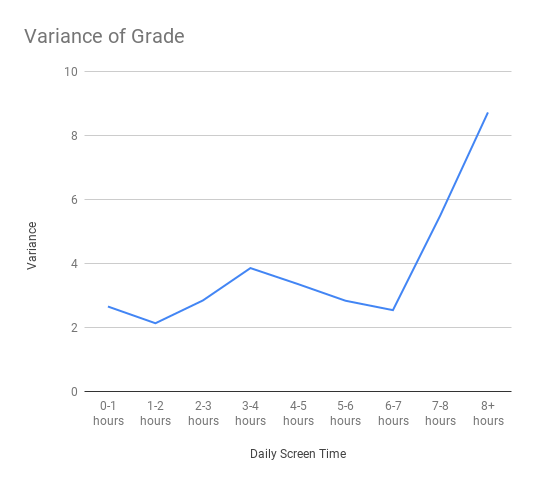

“I wanted to dig deeper and I actually found some interesting insights in terms of the variants—how much their grade would vary depending on screen time. I also looked at lowest overall grade per average screen time.

Main Findings

““In the first look, there wasn’t anything too compelling or anything that was aligned with what I expected before going into the survey.

“The three biggest findings that I uncovered were:

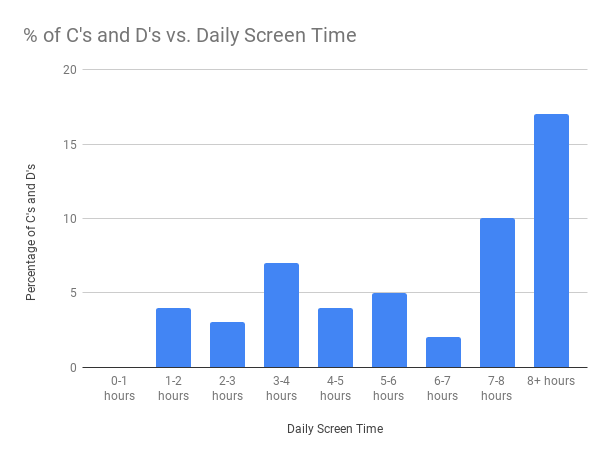

“First, no students who had 0-1 hours of screen time per day also had an overall grade of a C or a D. So these students that barely spent time on their phones, none of them had a C or a D. But when the screen time goes to 8+ hours, that number (who had low grades) skyrockets to 17%. It just shows that students spending more time on their phones had a higher potential to get a low grade.

“Second, students who spent 0-1 hours on their phone per day had very low variants. Their grades only varied by 2.5 points. When students spend 8+ hours on their phone per day, the variants shot up to 9 points.”

Je allocated one point to essentially one third of a letter grade. The difference between a B and a B+ was one point.

“The third biggest finding was lowest overall grade. The lowest overall grade for those who had 0-1 hours of screen time per day was B-. For those who had 8+ hours on their phone, their lowest grade was a D-. So it was quite a big difference there as well.

“Those were the three biggest findings I uncovered in terms of correlation between screen time and grades. Of course it’s not a causation. I don’t have enough data for that. But we did find there was a pretty decent correlation between screen time and grades.

“If I were to come to a conclusion about a causal relationship between screen time and grades, I’d first have to have a more comprehensive survey. The survey that I used for this piece was very short, very quick.

“If I were to do a study on causation, I would like to look more at what kind of apps respondents are using, whether it’s educational apps, or it’s just social media that’s taking up all their time, and seeing how much of their time is going to different categories. Besides that, I’d want to see how that behavior affects their semester grades as well, not only their cumulative grades. I’d want to see if, in one semester, they spent more time on their phones than another when they didn’t spend much time and compare the letter grades there. That would get us closer to a causation hypothesis.

“It is hard to say, because of course, there are so many different factors that can affect grades. But I think starting off with more data and more questions like the ones I mentioned, that would help us get to a causation hypothesis.

“It’s hard to say now, but I’d lean towards ‘more time spent on social media and ‘unproductive’ apps would have a negative impact on their grades.’ That’s time they could be using to study. It’s hard to say, but that’s what I would lean towards.

“I don’t think that it’s the best way to go about this. Now that everything has become more digitized—online textbooks and study material are available largely online—just generalizing screen time as one factor is the wrong approach to go about it. There’s so many different things that our devices allow us to do. If we’re not differentiating or specifying which apps or which purposes our devices are being used for, then it’s very hard and very incomplete to come to a conclusion that screen time has a certain effect. I think we should definitely be specifying what types of apps are having what types of impact and what types of devices as well.

“My study was just mobile phones, but I think it could vary largely depending on device.”

Featured Image: 贝莉儿 NG, Unsplash.

No Comments