Articles

New Adobe Study Highlights the Need for Creative Problem Solving in School

By Henry Kronk

March 12, 2018

Many have looked on the coming wave of automation with an attitude of dread. Many jobs will become entirely obsolete. Others will change so dramatically that professionals with decades of experience will need to leave their comfort zone and adapt. But when most people hear reports of an incoming tsunami, they get to high ground. In terms of automation, that means learning how to remain an effective worker and taking steps to achieve that end. Many trend watchers have pointed to skills such as social and emotional intelligence. A new study conducted by Adobe, however, highlights creative problem solving as an asset that machines won’t be able to replicate any time soon.

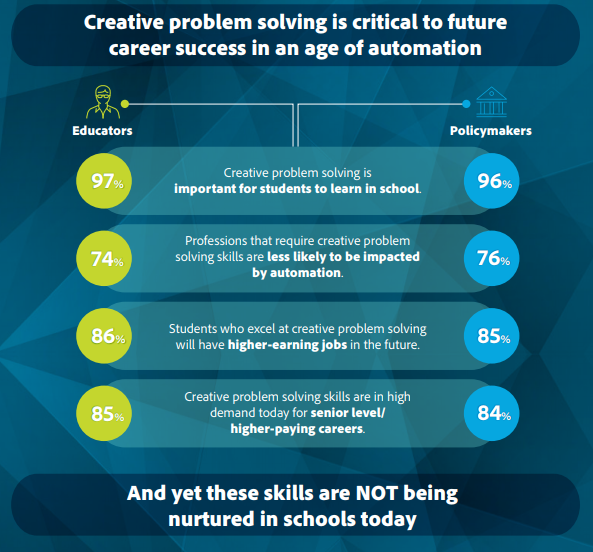

The company surveyed 1,600 secondary and post-secondary educators and 400 policymakers in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, and Japan to reach their conclusions.

The General Consesus? We’re Not Doing Enough

The quick and dirty results reveal a broad discontent with the amount of creative problem solving in education systems around the world. According to Adobe, 84% of educators feel there is not enough emphasis placed on the skill. With policymakers, that number sits at 68%.

What’s even more troubling is that many believe that curriculum currently in place doesn’t merely have a neutral effect. 80% of educators and 61% of policymakers believe that their students ability to exercise their own creativity to solve problems is limited by various factors.

While it is next to impossible for any policy to keep abreast of new developments in research and technology, most of those surveyed contend that education policy regarding creative problem solving has not changed at all in the last five years.

Many factors have brought about this gap between what educators and policymakers want and what they have to work with. These could include mandatory curricula, standardized testing, lack of tools or resources to emphasize the skill. Many also point to a lack of adequate training. The greatest single barrier cited by educators around the world, however, is the lack of time to effectively sow creative problem solving into their classes. Many teachers also find they struggle to come up with time to learn new software they could use.

“There is a clear gap between what educators and policymakers know tomorrow’s workforce needs, and what today’s students are learning in school,” said Tacy Trowbridge, who leads Adobe Education Programs, in a statement. “Educators, policymakers and industry—technology in particular—need to come together to improve opportunities for students. Creative technologies can help educators teach and nurture critically important ‘soft’ skills, and policies and curricula need to evolve to complete the equation.”

What’s to Be Done

There is also general consensus in what should be done about this issue. Only 20% of educators and 33% of policymakers believe that there should be a dedicated class for creative problem solving. Instead, most believe that the skill should be integrated into every subject.

The barriers to the necessary time, tools, and resources typically lie in a school’s funding situation. Over half of educators cited their school’s budget as a restraint to achieving the ends they envision.

One final issue in preparing for an automated world often goes unsaid: we don’t know what problems future workers will need to solve. As a result, educators and policymakers can’t do much more than foster a learning environment that emphasizes creativity. Despite the Adobe study, automation is still an abstract concept for many. Like climate change or inequality that plays out behind closed doors, it will be difficult for many to stare automation directly in the face until it has arrived.

No Comments