Articles

K-12

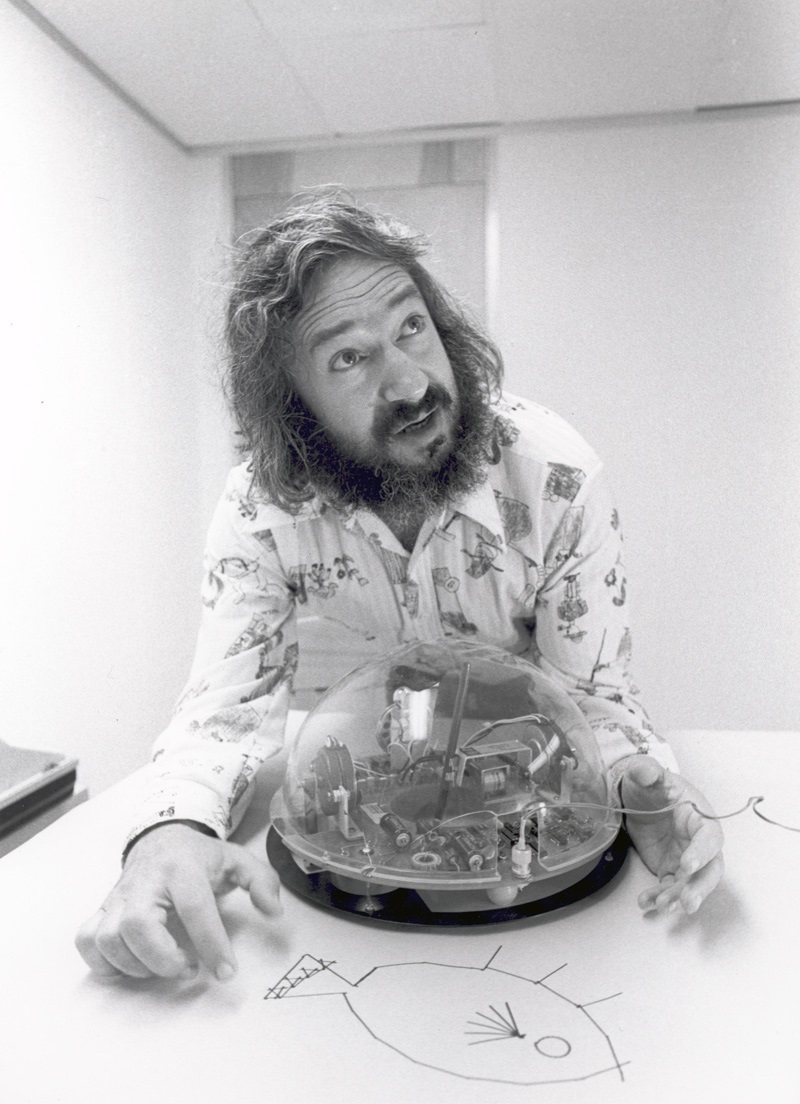

Seymour Papert, Logo Turtles, and the Origin of Educational Robots

By Henry Kronk

October 21, 2019

Dozens, if not hundreds, of products are available today that aim to teach children STEM subjects and computer science by programming robots. While these might appear as modern interventions, their use dates back nearly 40 years, and their concept is even older. Beginning in the 1960s, mathematician and innovative educator Seymour Papert conceived his Logo turtles, devices that would become the world’s first STEM educational robots.

In 1967, computer scientists Cynthia Solomon, Wally Feurzeig, and Seymour Papert teamed up to develop the programming language Logo. All three were working at the Cambridge, Mass. research firm Bolt, Beranek and Newman at the time. Logo was intended to make math and computer science simple and accessible to young learners, and to aid in math instruction.

Solomon, Feurzeig, and Papert Develop Logo to Make Math and Computer Science More Accessible

Initially, the language controlled an interactive graphic turtle in a simple computer program. Students could command it with simple terms such as ‘forward,’ ‘backward,’ ’left,’ and ‘right,’ along with a value corresponding to either distance or rotation. The command ‘pendown’ caused the graphic turtle to ‘draw’ a line where it has traveled. With these simple commands, students could use Logo to draw geometric shapes.

Beginning around 1980, Papert began integrating this language with simple robots, known also as ‘turtles.’ While Papert was a revolutionary educator, he was not the first to devise these devices. Educational robot turtles were first conceived by mathematician and computer scientist William Grey Walter to train upper-level students in CS in the 1940s.

Enter the Logo Turtle

During the 1970s, Papert began experimenting with turtle robot integrations with Logo. While many versions existed by 1980, Papert eventually used a circular turtle with two wheels, with the main function being computer-programmed movement. Following his digital turtles, Papert also included a retractable pen at its center that could be used to draw with the ‘pendown’ command.

Seymour Papert explained their use in his influential 1981 book Mindstorms:

In many schools today, the phrase “computer-aided instruction” means making the computer teach the child. One might say the computer is being used to program the child. In my vision, the child programs the computer and, in doing so, both acquires a sense of mastery over a piece of the most modern and powerful technology and establishes an intimate contact with some of the deepest ideas from science, from mathematics, and from the art of intellectual model building.

Papert believed that we live in a “culture that makes science and technology alien to the vast majority of people,” where students grow up thinking that devices like robots belong to “the others.”

This environment, to say the least, dissuaded young people from pursuing research in science, math, and technology. It created a ‘mathphobia.’ In response, Papert calls for the establishment of ‘Mathland,’ or a metaphoric country in which math is the native language, something that can be learned as one would learn French by living in France.

At the same time, Papert realized that, with the advent of digital technology, society and humanity at large stood at a crossroads. He wrote that “there is a world of difference between what computers can do and what society will choose to do with them.”

Educational Robots As a Cure for ‘Mathphobia’

His resulting proposition was to offer both the educational robots and the programming language that controlled them to students so that they might be accustomed to using Logo and other languages in the same way that they became accustomed to their own native language.

This idea coalesced in Papert’s idea of ‘constructionist learning.’ The pedagogy sought to retheorize learning as an activity that could be accomplished in numerous ways by a student, and not merely as a result of a teacher teaching a subject.

Reading Mindstorms in 2019 provides for an interesting perspective on how edtech and computer science education have progressed in the 38 years since it was published. Papert calls for every student to have access to a computer for their education. That has by and large come to pass, at least in North America.

What’s more, Mathland appears to be a metaphoric reality for a great many of schools today.

Seymour Papert passed away in 2016 at the age of 88. There remains a wide difference between what computers are capable of and how society chooses to use them. We can only wonder whether Papert would be pleased with the current direction edtech has taken.

Featured Image: Wikimedia Commons.

[…] Canada about to legalize marijuana, it is no surprise that Canadian institutions, including established […]